Edward’s Taxes

For any discussion of colonial taxes, it’s important to determine when and why they were levied. The New Hampshire colony started small with Piscataqua Plantation and other settlements on the Atlantic. Those took root between 1623 and 1641. A slow slide into the grip of Massachusetts Bay took place between 1641 and 1643, but the residents received an exemption from Massachusetts taxation and protection from royal patent holders in the area.[1] That did not, however, exempt them from paying taxes to support local infrastructure, churches, and schools.

Dover taxes

Local taxes were raised for community-wide benefits. They included property tax, a head tax (also called a poll tax) on adult males aged sixteen and older, an income tax, and taxes on specific items. Dover residents paid taxes based on wealth, which included personal and real property. Like other town residents, Edward paid his taxes with commodities such as wooden staves and easily stored food items because coins were in short supply in early New England. Then, as now, residents tried to have their property assessed for as little as possible, which meant paying less in taxes.

The taxes of Dover went for maintaining and making town improvements, supporting the local clergy, and eventually to schools. Edward also paid import and export duties as did other New Englanders. His sawmill was specifically assessed for the ship masts he produced.

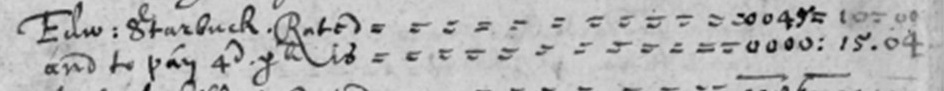

1648

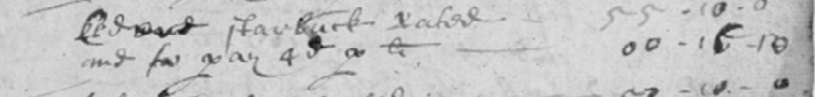

1649

Jul 1657

Nov 1657

1658

1659

Another kind of tax

Service to the town was expected of men in early New England, which can be seen as a type of tax. They took on community responsibilities such as helping divide the land or keeping up the roads without any pay. It was simply an expectation for any capable, adult male who moved into a village or town. While in Dover, Edward held the following positions:[2]

- Served as a representative to the General Court in 1643 and 1646

- Performed a survey of the town record books in 1646

- Served on a grand jury in 1647

- Surveyed land for others several times

- Was chosen as commissioner in 1658

On Nantucket he did the following jobs:[3]

- Laid out land

- Was manager of Native American relations in 1670 and other years

- Was nominated for a town military position in 1671

- Was nominated for magistrate in 1672

- Was chosen selectman and made a rate maker in 1673

- Was a magistrate in 1675

- Performed other town jobs for no pay

This was typical of all early New England towns where residents pitched in for the good of the community.

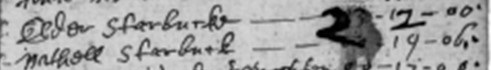

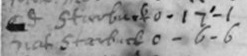

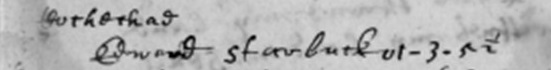

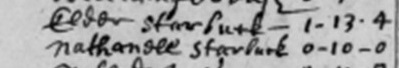

What Edward paid in Dover

While living in Dover between 1638 and 1660, Edward Starbuck appeared on six of the seven area tax lists.[4] He was absent from the 1650 list, but that may be due to missing pages or entries. The following table shows Edward’s tax payments, compared with the high, low, and average for each of the taxes levied in Dover. The various areas comprising much of Piscataqua Plantation were all taxed together, including Dover, Cochecho, Bloody Point, and Oyster River.

| Date | Edward paid | High[5] | Low[6] | Average | Number of payers |

| 19 Dec 1648[7] | £45 10s | £194 10s | £4 | £70 | 56 |

| 8 Dec 1649[8] | £55 10s and 16s 10d | £155 | £30 | £61 11s | 63 |

| 21 Jul 1657[9] | £2 12s | £9 15s 6d | 3s | £2 13s | 92 |

| 10 Nov 1657[10] | 17s 1d | £4 9s 9d | 1d | 17 s 5d | 93 |

| 12 Oct 1658[11] | £1 3s 5.5d | £3 3s 4d | 1s 8d | 17s 2d | 60 |

| 22 Nov 1659[12] | £1 13s 4d Same day/same page £3 6s 8d paid for the Great rate | £4 12s 2d | 4s | 15s | 141 |

Did Edward pay taxes on Nantucket?

By 1660, Edward was living in the town of Nantucket, also called Sherborne. There are no tax lists in the town records during Edward Starbuck’s lifetime. This was in keeping with the attitude of most early Nantucketers, that government and religion should both stay out of their business. Being an island off the coast had its advantages, making provincial tax imposition and regulation more difficult.

Things still got done in Nantucket despite the lack of taxes.[13] The community was small and the adult, white males met in homes as needs arose. There were no elected officials for many years and oversight was provided by the original proprietors, who included Edward Starbuck. When decisions were reached, individuals were appointed to carry them out. There is no record of community funding, though in time appointees were paid for more permanent jobs such as fence viewing or lot laying.

Something that could be called a type of tax was levied in 1673. The entry in the town records shows Edward, Tristram Coffin, and Thomas Macy were appointed “rate makers” for Nantucket.[14] In the terms of the day, they were enlisted to help establish taxes, and in this case the gathered funds went for powder and lead, presumably for defense.

Religious practices requiring the financial support of the townspeople were almost non-existent on early Nantucket.[15] It is difficult to define any religious practice on the island in the 1600s. When Massachusetts tried to assess a tax on Nantucket after gaining jurisdiction over it in 1692, the first thing the inhabitants did was to request an abatement.[16] That shows the attitude most islanders had toward a government or church which wanted their hard-earned profits.

What can we learn about Edward, Dover, and Nantucket through his tax records?

It’s clear from a study of the town records that Edward paid the taxes imposed on him while he was living in Dover. He started out paying less than average, but by the mid-1650s he was paying an average or above average amount, an indication his economic status had improved.

Once he was on Nantucket, Edward paid no taxes, at least no tax records have survived or been published for the island during the years he was there. While that makes it harder to assess his economic status, the fact that he was a founder, community leader, participant in town duties, contributor to the local economy, consultant on town issues, and arbitrator says a great deal about his community mindedness and status among peers even without tax records to show his contributions.

For a fuller explanation of Dover and Nantucket taxes, see Edward’s Taxes.

[1] Alvin Rabushka, Taxation in Colonial America (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2008), 150.

[2] D. Hamilton Hurd, History of Rockingham & Strafford Counties (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, J. W. Lewis & Co., 1882), 823; digital image, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com : accessed 31 March 2022).

Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 1, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E Jenks, state printer, 1867), 186; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 3 March 2022)

York, Maine, Record of the Courts Book 1 1636-1652: 99, Edward Starbuck, 1646; FHL DGS 5,654,540, item 1; digital image 110/208, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 11 May 2022).

Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, NH (www.dover.nh.gov/government/city-operations/finance/city-clerk-tax-collection/historic-dover-records: : accessed 10 August 2021).

[3] Nantucket, Massachusetts, Deed Book 1: 15, Edward Starbuck, 1669/70, FHL film 906,232, item 1, image 16/621; digital images, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 18 January 2022).

Nantucket, Massachusetts, Deed Book 1: 21, Edward Starbuck, 1671, FHL film 906,232, item 1, image 19/621; digital images, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 18 January 2022).

Nantucket, Massachusetts, Deed Book 1: 22, Edward Starbuck, 1672, FHL film 906,232, item 1, image 20/621; digital images, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 18 January 2022).

Nantucket, Massachusetts, Deed Book 1: 33, Edward Starbuck, 1672/73, FHL film 906,232, item 1, image 25/621; digital images, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 19 January 2022).

Nantucket, Massachusetts, Deed Book 1: 35, Edward Starbuck, 1673, FHL film 906,232, item 1, image 26/621; digital images, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 19 January 2022).

Nantucket, Massachusetts, Deed Book 2: 11, Edward Starbuck, 1674/75, FHL film 906,232, item 2, image 135/621; digital images, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 11 February 2022).

[4] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, New Hampshire, unpaginated, approx. p. 190, 1648 and others.

[5] The highest taxpayer for 1648 was Matthew Gyles. For 1649 it was Thomas Layton and Mrs. Mathes. Thereafter, every year the high taxpayer was Captain Waldren.

[6] The lowest taxpayer changed every year and was often one of the younger or newer town residents.

[7] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, New Hampshire, unpaginated, approx. p. 188-190.

[8] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, New Hampshire, unpaginated, approx. p. 183-186.

[9] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, New Hampshire, unpaginated, approx. p. 175.

[10] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, New Hampshire, unpaginated, approx. p. 174.

[11] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, New Hampshire, unpaginated, approx. p. 173.

[12] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, New Hampshire, unpaginated, approx. p. 170.

[13] Edward Byers, The Nation of Nantucket, 47.

[14] Nantucket, Massachusetts, Deed Book 1: 35, Edward Starbuck, 1673, FHL film 906,232, item 1, image 26/621; digital images, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 19 January 2022).

[15] Edward Byers, The Nation of Nantucket, 52.

[16] Edward Byers, The Nation of Nantucket, 127.