If I only spoke my name out loud, and didn’t tell you how to spell Keri-Lynn, how would you write it? I bet I can list at least 80 ways, and that’s retaining the hyphen in the middle.[1] Double that number for taking it out. Triple it if you retain the capital L in the middle. Over 200 spellings? That’s ridiculous for a modern given name, yet I’ve gotten most of them at one time or another.

The point is that if someone only hears a name, the writer must come up with a way to write it based on a) what he or she heard, b) what he or she knows of the accent/dialect of the speaker, c) what spelling conventions the writer is accustomed to using, and d) what he or she had for breakfast. That last one was courtesy of a paleography professor I had in 1977 who (jokingly) insisted breakfast choice was the primary reason for spelling differences prior to the twentieth century.

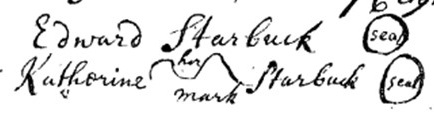

Think about it for a moment. Many, if not most, of our ancestors were illiterate or barely literate and dependent on others to write their names for them on deeds, probates, and court documents. They signed with a symbol, the X being the most common. Add in spellings from church, tax, and civil records and one person’s name might be spelled a dozen different ways during his or her lifetime.

It’s a simple historical fact that there was no standardized spelling for any word or name up to and including the early 1600s. The concept of standardization began to develop only after printing became more widespread. Visit the Spelling Society’s site for a tour of the history of spelling changes (http://spellingsociety.org/history#/page/1). The Spelling Society, historians, and The British Library all state 1755 as the year when standards were fully set, with the publication of Samuel Johnson’s dictionary.[2] Spelling variants in print had condensed down before then, but variation still abounded. In Edward Starbuck’s time (and the centuries before while surnames evolved) anyone who was literate could spell anything any way that individual wished. There was no consistency, not even among the educated who loved to vary the ways they named themselves and how they wrote. One person could write the same surname several different ways in the same document. All we can do is use our common sense and old-handwriting and spelling knowledge to judge when a scribe of an earlier day is writing the surname we’re seeking. Saying surnames aloud can help, though we also must remember there was no spelling conventions for certain sounds.

Compounding the lack of literacy for most of our ancestors is the fact that for colonial American records in particular, writers may have come from different areas of England, or perhaps Wales or Scotland, or maybe even Germany, Sweden, Holland, or France. The possibilities for recording a name from another dialect or language compounds the spelling variations and even mistakes. Mistakes? If spelling didn’t matter, what constituted a mistake? Writing a name down so it could not be pronounced in any way resembling how the name holder said it. It was a pretty low bar.

The key word when it comes to early spelling is pronounced. Any spelling that allowed a reader to get close to how an individual said his or her name was correct. There was no such thing as a wrong spelling if the name could be said to belong to its owner, and sometimes even if it couldn’t. Confusion due to spelling differences happened in the past, but it’s far more likely to happen to us today since we’re not open to “creative spellings,” or “alternate pronunciations.” We’ve been taught in school that there’s a right way to spell a name, but that is only true if the person spells the name himself or cares about how it is spelled.

Let’s take the surname Starbuck. The ubiquitous coffee chain has locked us into thinking there’s one correct spelling for Starbucks. The corollary is if you remove the final S, you have the “correct” spelling for Starbuck. While spelling the name “Starbucks” is right for the twenty-first century beverage retailer, but there was no standardized spelling for Starbuck in the seventeenth, let alone the sixteenth century, and for that matter no coffee either.

So, let’s put on our creativity caps and see if we can come up with some Starbuck variations. How about….

- Starbucke

- Starrbuck

- Starebuck

- Storebuk

- Sterbook

- Stairboke

- Starbocki (for the Latin language lover)

Now what if the speaker said something like, “Starrrr (rolling the r then pausing) Book?” Picture yourself as a university educated vicar writing an entry in the parish register for a baptism just performed for the infant of Mr. John Starbuck. He isn’t spelling his surname for you, so you write Starr Bucke in the register. It sounds like a two-part name, so perhaps it should be written that way. There was no law about having only one-word surnames, and for that matter no law against using just part of a surname, hence the Buck relatives who are closely related genetically to the Starbucks.

There are also parish register entries for names like Starbuck als. Johnson. Alias names happened for a variety of reasons, none of them criminal or deceitful. Most were due to keeping families differentiated or connected. At some point those using the surname might drop Starbuck, or Johnson. Then there are the abbreviations that may have been written at the time or used by later copyists. I’ve seen Starbuck transcribed as Starr:. If there’s only one person to fit the surname it could mean:

- The writer or transcriber was in a hurry

- The edge of the original document page was reached

- The writer or transcriber preferred using abbreviations where possible

- The page was torn and all that could be seen by the transcriber was “Starr”

The bottom line is that today’s family researchers must let go of the concept of right and wrong spellings. We must be open for any spelling which could, with a bit of imagination, represent a spoken name. Starbuck isn’t the only spelling in town, especially if you’re living in the seventeenth century.

[1] Keri-, Kari-, Kerri-, Karri-, Kerry-, Kery-, Kary-, Karry-, Carrie-, Carie-, Carey-, Carri-, Carrey-, Carie-, with -Lynn, -Lyn, -Lynne, -Lin, -Linn, -Linne. By mixing and matching these create 84 variations, and these aren’t all the spellings I’ve gotten.

[2] Wikipedia, “A Dictionary of the English Language,” rev. 02:02, 19 September 2022.

The British Library, The British Library, (https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/samuel-johnsons-a-dictionary-of-the-english-language-1755 : accessed 20 October 2022), Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language 1755.