The first two posts in this series showed Edward Starbuck was essentially a puritan, and that he also had a belief in credobaptism, for which he got into trouble with the Massachusetts Bay authorities. (See Parts 1 and 2.)

Edward’s adherence to believer’s baptism and the later association of the Starbuck surname with Quakers in both Dover and on Nantucket has led some family historians to label him a Baptist or Quaker. There was, however, no established Baptist or Quaker congregation in Dover nor on Nantucket during Edward’s lifetime, so it’s easy enough to answer this question with a simple, “no,” but this is also an opportunity to dive a little deeper into what it is about Edward’s life that caused some to connect him with those denominations.

Baptists

Edward arrived in Dover about 1638 and is connected to the establishment of the first church by Hansard Knollys.[1] Edward was one of the first Elders in the Dover church.[2] Hansard Knollys did not stay in Dover for long. Conflicts with another minister, Thomas Larkham, was a significant factor in Knollys’ return to England about 1641.[3] Knollys went on to work as a chaplain in Oliver Cromwell’s army, survived arrest during the Restoration, and then left England for a while.[4] Upon his return he preached in London, was arrested again, and later released. The doctrine he taught was most closely aligned with Baptist beliefs and he took part in efforts in the late 1600s to consolidate the Baptists. Edward’s association with Hansard Knollys coupled with his belief in credobaptism may have led some to believe he was a Baptist.

However, the first Baptist church in America was not organized until approximately 1638, when Roger Williams’s Providence congregation was labeled Baptist.[5] Although Baptist doctrine and congregations grew from there, Dover did not have a Baptist church until 1824 and Nantucket did not have one until 1841.[6] There were obviously individuals in Dover who held anabaptist beliefs before 1824, Edward being one of them, but they were not organized into a group calling themselves Baptists before 1824.[7] While Edward can be described as an anabaptist, and he was associated with the church Hansard Knollys established, it is too much of a stretch to call him a Baptist.

Quakers

The Quakers arrived early in Dover, and their congregation was the first non-puritan faith established there.[8] The first mention of Quakers in Dover history was in 1662 when three female Quaker missionaries came to Dover. They were treated very badly and were whipped out of town by a court order. This was in accordance with the Massachusetts Bay Colony law for driving Quakers from a town.[9] But the Quaker message took hold in Dover and by 1680 the first meeting was organized on Dover Neck. Historians have stated that at one time about a third of the town of Dover was Quaker, but that did not include Edward Starbuck. He, his wife, and younger children left Dover in 1659-60, before the first Quaker missionaries arrived.[10]

Nantucket Quakers

Nantucket is almost synonymous with Quaker whaling families. In the Heart of the Sea by Nathaniel Philbrick is one of many books which highlights this group of famous Nantucketers.[11] The Quaker connection to Nantucket goes back over three centuries to the early 1700s, and that connection was initially made by Edward’s close and direct descendants. Quaker missionaries visited Nantucket, possibly as early as 1698, and with greater frequency after 1700.[12] Edward Starbuck’s daughter-in-law, Mary (Coffin) Starbuck, and her husband, Edward’s son Nathaniel, became early proponents of the faith. Several of their family and island connections did as well. The first Monthly Meeting was held on Nantucket in June 1708 at the house of Nathaniel and Mary (Coffin) Starbuck. Although many of the Starbucks on Nantucket fully embraced the Quaker faith, Edward was not among them because he had passed away in early 1691, before the first Quaker missionaries came to Nantucket.[13]

Another Quaker Family Connection

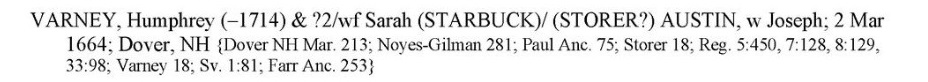

The Quakers had begun gathering in Dover in 1662.[14] Edward’s eldest daughter, Sarah (Starbuck, Austin) Varney was the first Starbuck to join the Quaker denomination. Her Quaker descendants include both her Austin and Varney children. Exactly when Humphrey and Sarah Varney joined the Quaker faith is open to conjecture, and it’s possible Sarah joined herself before marrying Humphrey Varney in 1664.[15]

The earliest Quaker missionaries to Dover (in 1662) may have piqued Sarah’s and/or Humphrey’s interest. Like Edward Starbuck, Humphrey also got into trouble for his religious practices. The record for a court held in Dover on 30 June 1663 states, “Humphrey Varney for not coming to meeting, pleaded non conviction, unto whome the Law was this day read & he admonished:”[16] This type of admonishment and, in some cases, fines were typical for Quakers who did not attend church.

Some family historians have reported that Humphrey refused to take an oath of allegiance, which was also typical of Quakers, but no evidence of that was found in Dover town records nor in any local or colonial court records. Several online pedigrees and family histories state Humphrey was buried in the Quaker cemetery in Dover, but no record of that interment exists. There are, however, two additional indications Humphrey was affiliated with the Quakers.

One is that Humphrey’s property bordered and possibly included the location used for the first Quaker congregation, established about 1680.[17] John Scales listed the location of the Quaker Meetinghouse in his history and showed it was next to Humphrey Varney’s home. It was not until much later that a purpose-built structure in another part of town belonging to the Quaker congregation was established. It’s quite possible a building on Humphrey’s property constituted the first meetinghouse.

The other indication is that Humphrey is identified as a Quaker in several local and family histories. [18] Several mention Humphrey’s connection to that denomination, though none state a specific source for that. Once the early Quaker records for Dover are digitized it may be possible to find more specific evidence.

Nantucket Associations

The first settlement on Nantucket (in 1659) had several founders/proprietors who had something in common with Edward Starbuck. Thomas Macy, Richard Swayne, Christopher Hussey, and Robert Pike were all on the receiving end of fines and worse due to the religious intolerance of Massachusetts Bay Colony. Thomas Macy’s “offense” was in sheltering Quakers from the weather, Richard Swayne was accused of “entertaining” Quakers, Stephen Hussey (son of Christopher) was accused of being a Quaker, and Robert Pike (a deputy at the time) had the audacity to accuse those who had made a law against preaching without a license of violating their own oaths.[19]

The Nantucket Historical Association describes the early religious affiliations of Nantucket’s earliest English residents as probably equal small numbers of Puritans and Baptists.[20] Proprietor Peter Folger shared a belief with Edward Starbuck. Before moving to Nantucket, he had traveled to Rhode Island where he was influenced by Roger Williams and embraced what was then known as antipedobaptism, the belief that adults, not children, should receive baptism.

The family of Tristram Coffin, the man who gathered the original proprietors together, was characterized as a pack of “Nothingarians.”[21] Other early Nantucketers, when pressed, identified themselves as “Electarians,” meaning that they elected not to associate themselves with any organized religion.

Although the early proprietors and residents of Nantucket held a variety of beliefs, the one thing they had in common, which was clearly important to them, was that they wanted to live in a place which granted them the freedom to believe as they wished without fear of punishment. Nantucket became a haven for those who had various, and no, religious beliefs. Whatever Edward’s beliefs can be termed, it’s reasonable to say he wanted to practice them without interference and wished others to do so as well.

Conclusion

Although Edward Starbuck had no affiliation with a Baptist or Quaker congregation during his lifetime, he had several family members who later became Quakers. His association with the first meetinghouse in Dover, established by Hansard Knollys who was later known as a Baptist plus his belief in anabaptism may cause some to mistakenly label him a Baptist. Edward was neither, though he showed a significant interest in religion and participated in the earliest established church in Dover. The desire to practice his beliefs in peace may not have been Edward’s only reason to move to Nantucket. Yet he uprooted himself and his family from Dover after establishing himself and living there for over twenty years. He definitely had significant reasons for his relocation, one of which may have been a desire for religious freedom.

[1] John Scales, History of Dover, New Hampshire (Manchester, New Hampshire: John B. Clarke Co, 1923), 126; digital image 147/548, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : 23 May 2022).

[2] N. E. Stiles, Manual of the First Church, Dover, New Hampshire Organized December 1638, (Dover, New Hampshire: N. E. Stiles Job Print, 1893) 15; digital images Internet Archive (www.internetarchive.org : accessed 10 August 2021).

[3] Rev. Jeremy Belknap, The History of New Hampshire, Vol. 1 (Dover, New Hampshire: S. C. Stevens & Ela & Wadleigh, 1831), 25-26.

[4] Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org: accessed 10 February 2023), “Hansard Knollys,” rev. 14:30, 22 October 2022.

[5] Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org: accessed 10 February 2023), “First Baptist Church in America,” rev. 20:44, 23 January 2023. Williams himself was primarily a Calvinist, according to the article, and the church later became a General Six-Principle Baptist church before migrating back toward Calvinism.

[6] John Scales, History of Strafford County and Representative Citizens (Chicago, Illinois: Richmond Arnold Publishing Company, 1914), 121.

Wikipedia, (www.wikipedia.org), “Timeline of Nantucket,” rev. 19:05, 1 August 2022.

[7] Among 17th century puritans or godly individuals (as they called themselves) in England were those who favored credobaptism while abhorring the idea of separating from the established church. It was a matter of ongoing doctrinal debate.

[8] John Scales, History of Strafford County and Representative Citizens, 114-115.

[9] John Scales, Colonial Era History of Dover New Hampshire (Manchester, New Hampshire: John B. Clarke, Co, 1923), 137-140; used 1977 facsimile reprint of original book by Heritage Books, Inc.

[10] Alexander Starbuck, History of Nantucket (Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1969), 17.

[11] Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org: accessed 10 February 2023), “In the Heart of the Sea,” rev. 19:30, 5 February 2023.

[12] Alexander Starbuck, History of Nantucket County, Island, and Town (Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1969), 518, 519-530.

[13] Nantucket, Nantucket, Massachusetts, Births, marriages, intentions of marriage, publishments, and deaths, ca 1662-1835: 4, death of Edward Starbuck, 1690/1 FHL film 906,220, item 1 image 10/257, digital images, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 24 February 2022). Also in FHL collection of Massachusetts Town Clerk, Vital & town Records.

[14] Dover Friends Meeting, QuakerCloud.org, (www.quakercloud.org/cloud/dover-friends-meeting: accessed 17 February 2023), The Quick Version of Who We Are.

[15] Clarence Almon Torrey, New England Marriages to 1700 (Boston, Massachusetts : New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2008), 1567; digital images, American Ancestors (www.americanancestors.org : accessed 22 July 2022). Sarah Austin to Humphrey Varney.

[16] Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 40, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E Jenks, state printer, 1867), 186; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 3 March 2022).

[17] John Scales, A History of Dover, New Hampshire (Dover, New Hampshire: Printed by the City Council, 1923), vii.

[18] Alonzo H. Quint, The First Parish in Dover, New Hampshire: Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary, October 28, 1883 (Dover, New Hampshire: Printed for the Parish, 1883), 50.

John Scales, A History of Dover, New Hampshire, 373, 374.

George Wadleigh, Notable events in the history of Dover, New Hampshire, from the first settlement in 1623 to 1865 (Dover, New Hampshire: Tufts College Press, 1913), 47; digital images, Internet Archive (archive.org: accessed 10 August 2021).

[19] Alexander Starbuck, History of Nantucket (Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1969), 14.

[20] Nantucket Historical Association, Nantucket Historical Association (www.nha.org : accessed 23 February 2023), “When Did Nantucketers Become Quakers?”

[21] Nantucket Historical Association, “When Did Nantucketers Become Quakers?”