What jobs did 1762 William Duke have?

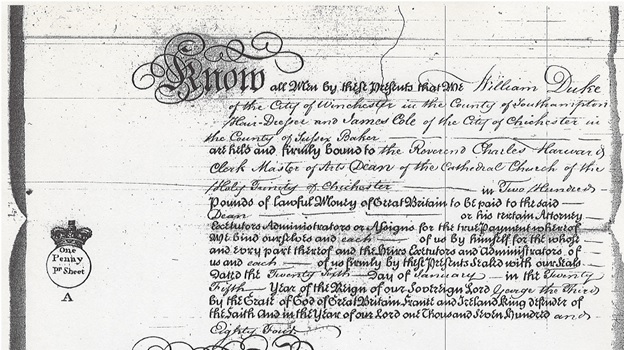

There is ample evidence 1762 William Duke (1762-1803, husband of Anne Barnes and father of 1796 William Duke) was associated with two occupations during his lifetime, as noted in various documents. The earliest evidence is his marriage bond.[1]

The marriage bond specifies, “William Duke of the City of Winchester in the County of Southampton Hair-Dresser…” This is documentation of an occupation in 1785. After marrying, William Duke and Ann (Barnes) Duke moved to the town of Derby. There were indications of William’s continuing his hair-dressing occupation in a newspaper article about a petition to prevent the selling of hats, gloves and perfumes without the stamp required by an Act of Parliament.[2] William’s name appeared on the 1792 petition because hairdressers were often perfumers as well.

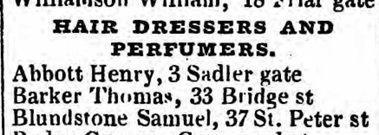

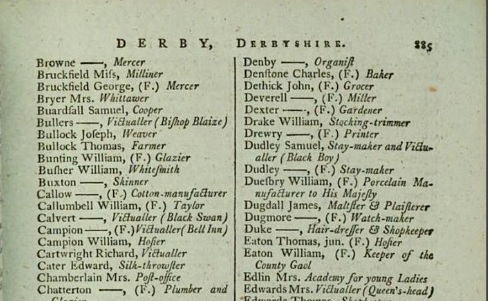

Businesses in the eighteenth century often diversified. How common it was for hair dressing and perfume makers to be connected can be seen in directories which list the occupations together:

William’s connection to hairdressing was also in a 1791 directory.[3] As with many of the others in Derby, his given name was not listed, but there were very few Dukes in Derby in that time (see William Duke in the 1820s part 1), and all of them were related. At that time, the only Duke with a hairdressing business was William.

No local or national trade directories covering 1792-1803 were found. However, at some point in those eleven years, 1762 William changed his focus. In 1803, William Duke died and his wife, Ann, took out the administration for his estate. The occupation listed for William was “confectioner.”[4]

William or Ann (female-operated businesses were often listed under their husband’s or father’s names) may have had the specialized training needed for these occupations, but there is a more logical explanation for an apparent drastic occupational shift, especially later in William’s life.[5]

One thing can explain both of William’s documented occupations. If he was an owner of businesses which employed skilled labor he could be listed as a hair-dresser or confectioner himself in a directory. A businessman could own a variety of shops over his lifetime, selling and buying or starting new businesses to meet consumer demand. It is difficult to tell from trade directories and newspaper articles alone if an individual was an employee or employer. The same terms were used for both. The fact that entries in directories had to be purchased, asks the question of who would benefit from having a directory entry? While skilled laborers might want to have themselves listed in an early version of Linkedin, and might be able to pay for that, business owners would benefit the most from advertising a business and where it was located.

By the early 1800s, the cultivation and manufacture of cane sugar from the West Indies and tropical parts of the Americas had taken hold and processing refinements made affordable sugar more available.[6] Sweet shops, as they came to be called, proliferated in Britain.[7] Opportunity and demand lined up, creating motivation for William to switch to or add on a confectionery, a logical business move at that time.

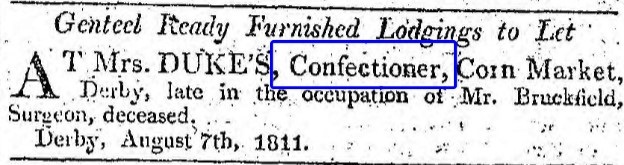

After William’s death, his widow, Ann, continued running the confectionery business until at least 1811 when she appeared in an advertisement in the Derby Mercury as a Confectioner.[8]

By 1822, Ann Brentnall, the daughter of William and Ann (Barnes) Duke had taken over the family business.[9]

From these various sources, it is apparent that William Duke was involved in hairdressing and confectionery, most likely as a small business owner/operator. Yet Minard’s Allegany County and its People and Mott’s The Story of Erie both identify 1762 William with the making of lace.

Mott’s history on 1830 William (eldest son of 1796 William Duke) stated his father came to “this country from his native Derbyshire April 26, 1820. In England the elder Duke was for years identified with the making of handmade lace and was among the first to introduce machinery into this important business.”[10] Minard’s history stated, “Mr. Duke (referencing 1796 William) conducted in England the making of handmade lace, a business presumably handed down from his father (referencing 1762 William), but the introduction of lace-making machines caused the ruin of the hand industry about 1820. Mr. Duke not long after came to America…”[11]

With no documented evidence of 1762 William Duke making handmade lace, or running a lace-making business, was there any connection between the Dukes and the lace industry?

Handmade lace in Derbyshire

For centuries, lace was made by hand, using bobbins and pillows. There were specific lace making areas, and by the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries bone or pillow lace was centered on Northamptonshire, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, and Oxfordshire.[12] From there the industry spread south into Wiltshire, Somersetshire, Hampshire, Dorset, and secluded valleys in Devon – especially Honiton, famous for the quality of its bobbin-lace. There were offsets in Wales, Yorkshire, and isolated efforts on various islands, but the point is that Derbyshire did not have a handmade lace industry. One author stated only a small amount of pillow lace was made in the county, the type and amount generally used by the maker herself or sold to friends and neighbors.[13]

Stuart King, Bone up on Bobbins: the craft of lace bobbin making (https://stuartking.co.uk/bobbin-making/ : accessed 13 September 2024).

Machine-made lace

The Industrial Revolution brought a profound change in lacemaking. By the late 1700s, another industry, that of framework knitting, had taken hold in Nottinghamshire, the county east of Derbyshire, and spread out from there.[14] Framework knitting primarily produced stockings, but because fashions came and went, an effort was also made to produce a lace-like product using framework knitting techniques. It took many years of refinement, but eventually framework knitters were able to produce the net-look of lace. The cheaper and faster production of lace revolutionized the industry. By 1818 the earliest patents had run out and bobbin net fever took hold as everyone tried their hand at making bobbin net machinery. Entrepreneurs made constant improvements to the machines, developing increasingly complex designs and steadily taking over the lace industry.

Barrow Upon Soar Heritage Group, The Organization of the Industry, (https://www.barrowuponsoarheritage.org.uk/articles/village-history/local-history/history-of-framework-knitting/the-organisation-of-the-industry.html : accessed 13 September 2024), “Framework knitters”.

Derby became one of the centers for machine-made lace. This can be seen from the directories for Derbyshire which shifted toward the mechanized knitting that became the springboard in the production of manufactured lace. The Universal Directory of 1791 had no handmade lace producers in Derby, but the town did have four framework knitters (most likely employers of those who did the actual work) and one frame smith who presumably made the frames that were needed. [15]

A directory for 1811 showed one “manufacturer of hosiery & British lace,” four “manufacturers of hosiery,” in addition to merchants selling hosiery.[16] The next directory found was Pigot’s 1818-1820.[17] The listings for Derby included three frame smiths, eight hosiery manufacturers, and one lace manufacturer and warehouser (same person). In Pigot’s 1822 directory, there were four frame smiths and eleven hosiery manufacturers. The likely reason the framework knitters themselves were not named individually was because the cost of being listed in a trade directory was a luxury the knitters did not have. The saying, “As poor as a stockinger,” was common during the nineteenth century, a reflection of how little the knitters were paid.[18]

Patents

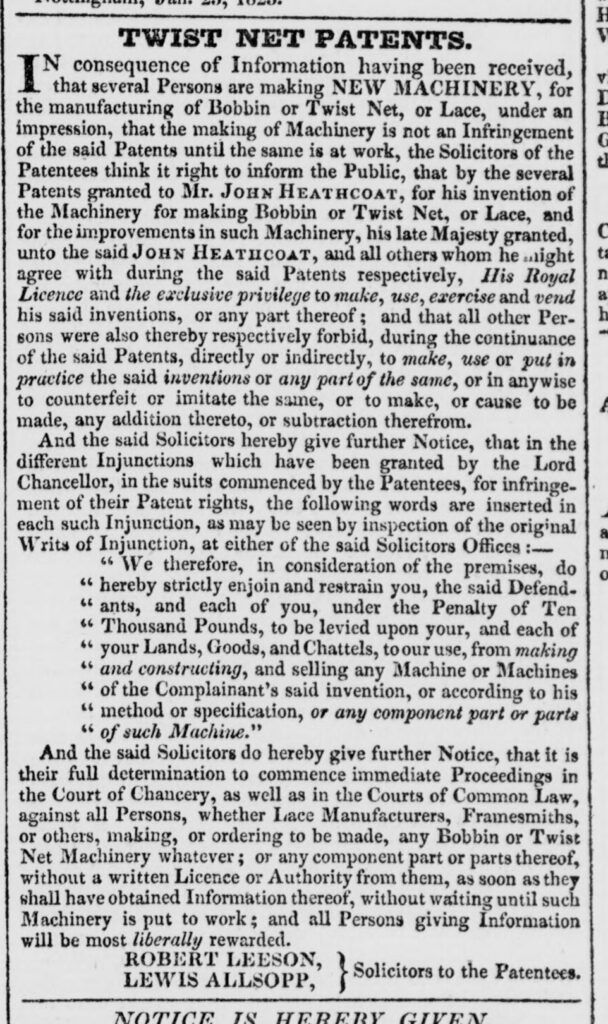

The growth of the industry can be seen in the issues associated with its expansion. Though some patents on the machinery had run out, at least one important patent on the machine which could create the lace (also known as bobbin or twist net) had not run out in 1823, though some thought it had, as can be seen in an article in the Derby Mercury.[19]

A meeting was held shortly after the patent reminder was published decrying the illegal practice of making new machines instead of using the licensed, patented ones.[20]

The problem of using unauthorized machinery continued. A public notice was published in September 1823 advertising a reward of 200 guineas for anyone who furnished information on patent infringers that led to a conviction.[21]

The multiple articles published over a period of nine months in 1823 are only a small selection of notices and news in the Derby Mercury in the 1820s regarding the making of twist net lace and its machinery. The way the industry blossomed can further be seen in Pigot’s 1828 Derby directory which listed two frame smiths, eleven lace manufacturers (including a John Duke whose connection to 1762 William is yet unknown), three lace warehousers (including a Caleb Cockayne whose connection to Elizabeth Cockayne is unknown), and twelve hosiery manufacturers.[22] The industrial production of lace and hosiery using the framework machines, called twist net machines, became a major industry in Derby in the 1820s.

Speculation

In 1829, Stephen Glover published a history of Derbyshire.[23] He wrote two paragraphs about lace manufactories in Derby, which stated:

“The largest of this description is the one in Castle-street, belonging to Messrs Boden and Morley. It is a handsome structure, containing 298 windows & occupying an area of 2124 square yards. The principal building is 56 yards long. It is fitted up with 150 machines worked by steam power, and contains an engine of 20 horse power, planing engine, casting, fitting-up and winding rooms, smiths’ shops, and every convenience for such an establishment. This is not only considered the largest establishment of the kind in the kingdom, but the most complete as regards the machinery, which has been principally constructed under the direction of Mr. Morley. It would be a difficult task to give a correct idea of the numerous and complicated movements of the beautiful machinery here employed. The next manufactory of importance of this description, is that of Mr John Johnson in Albion Street. There are also several smaller manufacturers.

“The manufacture of the beautiful fabric called bobbin net-lace has been introduced into Derby within the last ten years. Nottingham and Loughborough were some years the chief marts for it. Very extraordinary profits was obtained on its first introduction. This induced numbers who could raise a little capital to embark in it. The great demand for machines caused them to rise five or six times above their real value. Many tradesmen, who had been travelling steadily on in the old beaten tract, fancied they saw golden days at hand. The bobbin net machine was to be the means of realizing to the possessor a rapid and splendid fortune. In the brilliant prospect the speculative mind became dazzled, and head giddy with the thought of purchasing estates, building mansions and driving four in hand. The picture was too glowing to be real. The scene, alas! Soon changed; many soon found they had speculated their all, and that all had surreptitiously sunk into oblivion. Others withdrew from the trade at immense sacrifice. Lace manufactories and machinery became a drug in the market. A machine, which had originally cost from £600 to £800 might be purchased for £100. The article manufactured fell in proportion, and the trade became vested among capitalists and the most eminent mechanics.”[24]

This machine lace controversy with its financial fallout could be the real genesis of the lace issue which pushed 1796 William Duke toward America.

A connection to 1796 William?

There is no evidence from printed sources to connect 1796 William to a failing hand-made lace industry. There was no handmade lace in Derby during his time there, but machine lace abounded, and that industry had its ups and downs, including the brief money-making bubble described by Glover with the production and selling of lace-machines.

Mott and Minard both stated incorrectly that 1796 William was connected to the handmade lace industry, but if they were told or guessed the lace industry underwent a financial depression, they may have assumed the cause was the shift from handmade to machine-made lace. The authors might have used the same mistaken source, or one relied on the other, but the lack of handmade lace in Derby is conclusive.

Nevertheless, it may very well be that 1796 William was connected to the volatile lace-machine speculation and a setback in such an investment was a push factor towards trying his luck in America. Evidence of a financial loss that may have occurred two hundred years ago is unlikely to exist, nevertheless it could have been one of the reasons for William’s immigration.

[1] Marriage bond of William Duke with James Cole, 26 January 1785, Cathedral Close Collection, no reference given, procured from West Sussex Archives by Alexandra Barford August 2013.

A marriage bond and allegation are documents that were created when a couple applied for a marriage license. They were not created for couples who married by banns. A bond included a financial penalty for the groom and his bondsman if the allegation was found to be false (eg. either party already married, or underage). The bondsman was usually a close friend or relative of the groom.

[2] “Resolutions Respecting the Stamp Duty on Hats, Gloves, and Perfumery,” Derby Mercury, 4 October 1792, page 4 column 1; imaged, “Derby Mercury, (Derby, Derbyshire, England,) Newspapers.com (www.newspapers.com : accessed 19 June 2024).

[3] The Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce and Manufacture Volume the Second (London, England: The British Directory Office, 1791), 885; imaged, Google.com/Books (www.googlebooks.com : accessed 30 August 2024) image 887/924.

[4] Prerogative Court for the Bishop’s Court of Lichfield, B/C/11, Administration of William Duke, 1803 ; Staffordshire Record Office, Stafford, England.

[5] Usually only widows or independent single women would be listed under their own names in Directories

[6] Wikipedia, (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_sugar), “History of Sugar,” revised 12:16, 11 September 2024).

[7] BBC, The bittersweet history of confectionary, (bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zm2q4xs : accessed 12 September 2024).

[8] “Genteel Ready Furnished Lodgings to Let,” 8 August 1811, page 3 column 3; imaged, “Derby Mercury, (Derby, Derbyshire, England,) Find My Past (www.findmypast.com : accessed 6 September 2024).

[9] Unknown author, Derbyshire Directories, Pigot’s Directory 1822-3 (title page not photographed), 39; photographed by Celia Renshaw: accessed 12 June 2024 from shared file.

[10] Edward Harold Mott, Between the Ocean and the Lakes: The Story of Erie (New York, New York, John S. Collins, Publisher, 1899), Men of Mark in Erie Towns, William Duke, 103.

[11] John S. Minard, author: Georgia Drew Merrill: editor, Allegany County and its People (Alfred, NY: W. A. Ferguson & Company, 1896), 403-405.

[12] Mrs. Bury Palliser, The History of Lace (New York, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902), 371-373; imaged, Internet Archive (www.archive.org : accessed 9 September 2024).

[13] Most pillow and bobbin-lace (also termed bone lace) was created by women, but men also did lace-making. During strong periods for the industry, lace-making could pay more than agricultural labour.

[14] Mrs. Bury Palliser, The History of Lace, 447-450.

[15] The Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce and Manufacture Volume the Second (London, England: The British Directory Office, 1791); imaged, Google.com/Books (https://play.google.com : accessed 30 August 2024).

[16] Holden’s Annual London and County Directory, of the United Kingdoms, and Wales, in Three Volumes, for the Year 1811, Vol 1-3 (London, England: W. Holden, 1811), 122-126; photos of Derby taken by Celia Renshaw.

[17] “UK, City and County Directories, 1766-1946,” database with images, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com : accessed 27 August 2024), search term William Duke; citing p. 146 of Pigot’s Directory 1818, 1819, 1820.

[18] Barrow Upon Soar Heritage Group, History of Framework Knitting, (barrowuponsoarheritage.org.uk : accessed 11 September 2024) “Social Consequences.”

[19] “Twist Net Patents,” 29 January 1823, page 1 column 4; imaged, “Derby Mercury, (Derby, Derbyshire, England,) Find My Past (www.findmypast.com : accessed 11 September 2024).

[20] “Twist Net Patents,” 29 January 1823, page 1 column 2; imaged, “Derby Mercury, (Derby, Derbyshire, England,) Find My Past (www.findmypast.com : accessed 11 September 2024).

[21] “Twist Net Machinery,” 10 Sep 1823, page 1 column 1; imaged, “Derby Mercury, (Derby, Derbyshire, England,) Find My Past (www.findmypast.com : accessed 11 September 2024).

[21] “Twist Net Machinery, Rotary Patents” 3 Sep 1823, page 1 column 1; imaged, “Derby Mercury, (Derby, Derbyshire, England,) Find My Past (www.findmypast.com : accessed 11 September 2024).

[22] Pigot and Co’s, compiler, National Commercial Directory for 1828-9 Cheshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Shropshire (London, England: Pigot & Co, 1828-9), 125-132.

[23] Steven Glover, The History, Gazetteer, and Directory of the County of Derby Part 2 (London, England: Henry Mozley & Son, 1829).

[24] Steven Glover, The History, Gazetteer, and Directory of the County of Derby Part 2, 426.