Although the previous post asserted Edward Starbuck was a puritan, that term is nebulous in colonial America. By the 1640s, the English Reformation (Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church) had been evolving for over 100 years.[1] The monarchs covering that span had variously supported and tried to reverse the course of religious reform. It is little wonder the average members of the Church of England espoused a variety of religious concerns. Those who wanted to see the services and ordinances of the church less ritualized and more “pure,” gained support from both commoners and gentry. However, by 1633 William Laud was the Archbishop of Canterbury and he was pushing back against those who supported reform, with the aim of imposing his Arminian forms of worship.[2]

Separatists and Puritans

Two groups in particular, the Separatists (who founded the Plymouth Colony) and Puritans (who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony) left England respectively in 1620 and 1630. They both left for religious reasons, but those reasons were not identical. The authorities fined and imprisoned Separatists to the extent than many had to leave England, fleeing first to Holland and then to what became Plymouth Plantation. They did not want any nationally established Church of England.

The Puritans also disagreed with how things were being done, but it was mostly their clergy who faced Laud’s penalties including the loss of their livings. The clergy’s more ardent followers often traveled with them to the New World to escape Laud’s regime. They still saw themselves as members of the Church of England, and did for some time after immigrating, but they wished to rid themselves of the Arminian version of the church that Laud and Charles I espoused. They wanted the freedom to worship as they believed it should be done. John Winthrop, governor and leader of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, used these words to describe the goal for his colony, “For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us.”[3]

Yet despite Winthrop’s ideals, many of them shared by fellow puritans, there was no universal, well-developed, doctrine for puritans.[4] They all sought freedom faith and economic opportunity, but puritan beliefs were more about what they did not want to have at church. That included a lot of ritual or popery as they called it, preachers who failed to teach the Bible properly, the ungodly sharing the Lord’s Supper (communion) with the godly (as they termed themselves), and improper Sabbath observance.

Although the puritans shared a desire to purify the Church of England from what they regarded as papist (Catholic) and ungodly practices, they could not tolerate Laud’s reforms, resulting in wide differences, debates, and arguments amongst themselves over how to conduct the “right” form of worship. Being mostly of an Independent (Congregational) leaning, puritans favored the belief that each person could have a direct “covenant relationship” with God which was best accomplished in the “right” church. But what exactly that “right” church would teach was not clearly defined, leaving room for various beliefs to emerge.

Not long after the Separatists’ and Puritan’s arrivals dissent within their own construct began. Two of the most famous dissenters from the “New England Way,” or puritan cause, were Anne Hutchinson who preached Antinomian beliefs (salvation by grace) and Roger Williams who was convicted of sedition and heresy for spreading “diverse, new, and dangerous opinions.”[5] Both were convicted and banished for their beliefs, Hutchinson in 1637 and Williams in 1635. Clearly there were a lot of differences of opinion amongst the puritans, though the colony of Massachusetts Bay did all it could to ensure conformity to its leadership’s own brand of puritanism.

Dover’s Dilemma

Once Dover came under the jurisdiction and laws of Massachusetts Bay in 1643, puritan thoughts and ideals were enforced. What as a crime in Massachusetts was now a crime in Dover. Some of the laws were quite severe with capital punishment inflicted for many crimes that carried lesser sentences a few decades later. Massachusetts Bay Colony professed its support for strict, moral behavior which included forbidding any heathenish and idolatrous practice, going so far as to require certain types of dress and short hair for men.[6]

In these ways, the Bay Colony practiced a disciplined and often punitive ‘theocracy’ (a combination of church and state). Although early dissenters against this form of governance, such as anabaptists, were initially left alone (considered to be too small to be consequential), by the 1650s when the Quakers appeared, punishments were often cruel in the extreme.[7] They suffered degrading public punishments such as whippings and court trials which imposed banishments or death penalties for preaching or espousing doctrine outside the prescribed forms dictated by Massachusetts Bay. By the mid-1630s, court trials appear in the colonial records for any who taught doctrine outside the prescribed instruction as overseen by the leadership of Massachusetts Bay.

Edward Starbuck’s Anabaptist Trouble

Edward Starbuck got his own taste of life under strict puritanism on the third of October 1648 when, “The Grand Jury presented Edward Starbuck for disturbing the peace of the church, and refusing to join with it in the ordinance of baptism; for which he was admonished and discharged.”[8] From that description, it appeared Edward was going to get off easily, but in another document dated the same day, Edward was required to bind himself for a sum of £40 to make a personal appearance at the next Court of the Assistants held in Boston on the first Tuesday of December.[9] Furthermore, he was bound for another £10 to “this Jurisdiction” (Dover) for “peaceable and good behavior towards all men and especially towards the Reverend teacher of Dover.” Edward also received a fine of 2 shillings and 6 pence.[10]

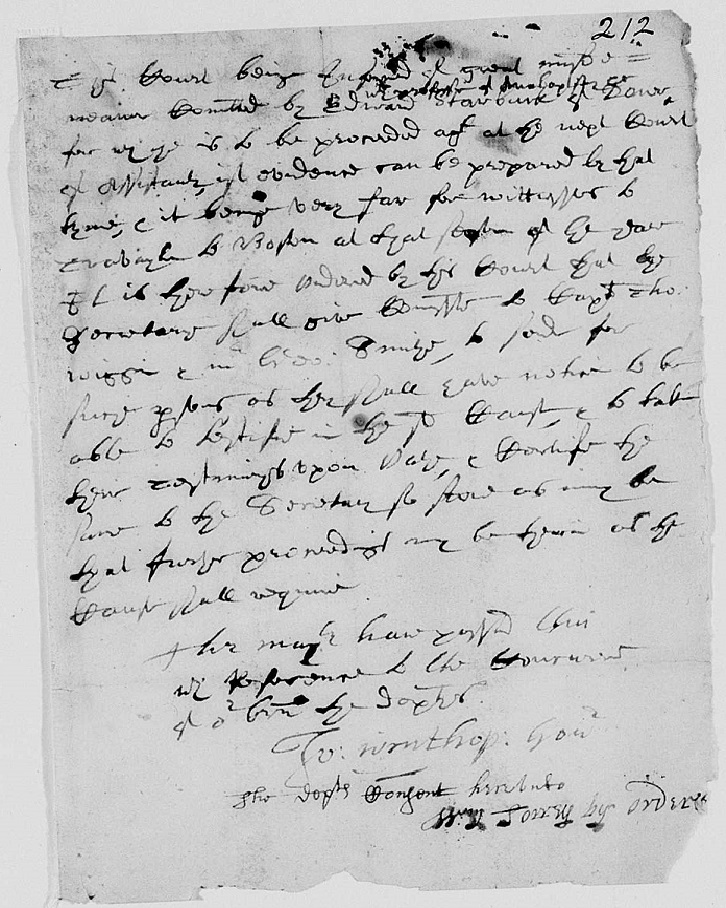

This Court being informed of great mysde =

mener Committed by Edward Starbuck of Dover with professor of Anabaptiser

for whiche is to be proceded of at the next Court

of Assistants if evidence can be prepared by that

tyme, & it beinge very far for witnesses to

travayle to Boston at that season of the year

& it is therefore ordered by the Court that the

Secretary shall give Comm[ission] to Capt Tho:

Wiggin & Mr Edw: Smithe to send for

such persons as they shall have notice of To be

able to testifie in the s[ai]d Court & to take

their testiminonies upon oath & Certifie the

same to the Secretary so s[oon] as may be

that further proceedings may be therein as the

Court shall require

The magts (magistrates?) have testif’d this

with Reference to the Gouvneur

Of our [ ]n the depties

Jo: Winthrop : Govr

The depts. Consent hereunto

Wm. Torrey by orders

Anabaptism in colonial New England was not a central tenant to any denomination as it was for some in continental Europe. [11] As seen in New England records, anabapitsm was essentially the early Baptist doctrine of believer’s baptism or credobaptism, which was that infants did not need baptism, but adults who could profess their faith and join a community of believers did.[12] It was the kind of “dangerous opinion” Roger Williams held, because he was baptized as an adult after his banishment to what would become the Colony of Rhode Island.[13] From the court documents, it appeared Edward had gotten himself in trouble for a similar belief, possibly contradicting Daniel Maud’s teachings on infant baptism or perhaps not baptizing his own child.

Further trouble came for Edward on 14 October 1648.[14] The General Court of Massachusetts Bay reiterated the Grand Jury’s presentment that Edward was to be proceeded against at the next Court of Assistants in Boston if sufficient evidence could be prepared by then and travel was possible. Captain Thomas Wiggin and Mr. Edward Smyth were also commissioned to send for those could testify in the case and to take their testimonies by oath as they might be needed. An asterisk within the transcription for that document in the New Hampshire State Papers also referenced a previously declared condemnation for the wearing long hair “after the manner of ruffians and barborous Indians,” a possible indication Edward was in trouble for that violation as well.

Edward Isn’t Punished

So, what happened next? Apparently, nothing. No more evidence of a trial or outcome is in the New Hampshire State (Provincial) Papers, the Massachusetts Court of the Assistants records, nor any other court or town records. Perhaps the matter was dropped because travel to Boston wasn’t possible in December 1648 and the case wasn’t deemed important enough to reschedule. Perhaps there wasn’t enough evidence, or no one would come forward to testify. Additionally, Dover had gotten assurances from Massachusetts Bay Colony before their merger that they could retain their autonomy in some ways including allowing residents to participate in town affairs regardless of church membership. That may have extended to a passive resistance shown by the residents, an indication they felt Massachusetts Bay Colony had no jurisdiction over local religious matters.[15]

Another possibility derives from what life was like in early New England. It was frontier living where everybody and their skills were needed. Edward was particularly skilled at constructing weirs and sawmills, and is shown by documentary evidence to be doing both by 1648.[16] Dover may have been reluctant to lose him and his unique talents. Edward’s weir was also supporting the local church and its minister.[17]

What it all came down to is that Edward received no punishment other than the 2 shilling, 6 pence fine. He may even have gotten some or all of his bond money back as it appears he was not required to travel to Boston. Unfortunately, there is no way to know anything more in the absence of additional records.

In the final analysis, we can state he believed in anabaptism, and stood up for that belief. With multiple doctrinal disagreements in colonial New England it is still possible to label him a puritan, in spite of his opinion concerning baptism. But did his belief make him a Baptist, or possibly a Quaker? Read part three.

[1] Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org), “English Reformation,” rev. 10:07, 6 Feb 2023.

[2] Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org), “William Laud,” rev. 22:53, 10 Jan 2023.

[3] Edmund Clarence Stedman and Ellen Mackay Hutchinson, eds, A Library of American Literature: Early Colonial Literature From the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time, (New York, New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1888), 307.

[4] Michael P. Winship, “Were There Any Puritans in New England?” The New England Quarterly, 74 (March 2001): 118-138, specifically 123; image copy, JSTOR (www.jstor.org: accessed 9 Feb 2023).

[5] Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org), “Anne Hutchinson,” rev. 12:52, 17 Jan 2023.

Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org), “Roger Williams,” rev. 12:52, 17 Jan 2023.

[6] Rev. Jeremy Belknap, The History of New Hampshire, Vol. 1 (Dover, New Hampshire: S. C. Stevens & Ela & Wadleigh, 1831), 41-42.

[7] Rev. Jeremy Belknap, The History of New Hampshire, Vol. 1, 47-49.

[8] George Wadleigh, Notable events in the history of Dover, New Hampshire, from the first settlement in 1623 to 1865 (Dover, New Hampshire: Tufts College Press, 1913), 29; digital images, Internet Archive (archive.org: accessed 10 August 2021).

[9] Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 40, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E Jenks, state printer, 1867), 40; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 3 March 2022).

[10] Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 40, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E Jenks, state printer, 1867), 42; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 3 March 2022).

[11] Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org), “Anabaptism,” rev. 02:31, 14 Jan 2023.

[12] Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org), “Believers Baptism,” rev. 13:49, 29 Jan 2023.

[13] Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org), “Roger Williams,” rev. 12:52, 17 Jan 2023.

[14] Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 1, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E Jenks, state printer, 1867), 191-192; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 3 March 2022).

[15] The full agreement between Massachusetts Bay Colony and Dover is printed in Historical Memoranda Concerning Persons and Places in Old Dover vol. 2 by Rev. Dr. Alonzo Quint, edited by William Edgar Wentworth pages 64-66. The wording of the pertinent item in the final court order passed 9 October 1641 stated, “It is ordered, that all the present inhabitants of Piscataq who formerly were free there shall have liberty of freemen in their several townes to manage all their town affairs & shall each towne send a deputy to the General Court, though they bee not at present church members.” This raises the question of how much jurisdiction Massachusetts Bay had over church-related affairs since residents were to have the liberty of freemen and did not have to be members of a church to be deputies to the General Court.

[16] Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 40, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E Jenks, state printer, 1867), 454-455; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 3 March 2022).

Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, New Hampshire (https://www.dover.nh.gov/government/city-operations/finance/city-clerk-tax-collection/historic-dover-records/ : accessed 10 August 2021), 3.

[17] Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 40, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E Jenks, state printer, 1867), 454-455; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 3 March 2022).