Starbuck/Waldron Timber at Thompson’s Point

Edward Starbuck and Richard Waldron were in a bit of hot water in June of 1647 with their logging business.[1] The land Edward and Richard were on was known as Thompson’s Point.[2] There was more than one place with that name, but this one was on the northeast side of the Piscataqua in what is now Eliot, Maine, which was part of Kittery in the 1600s.

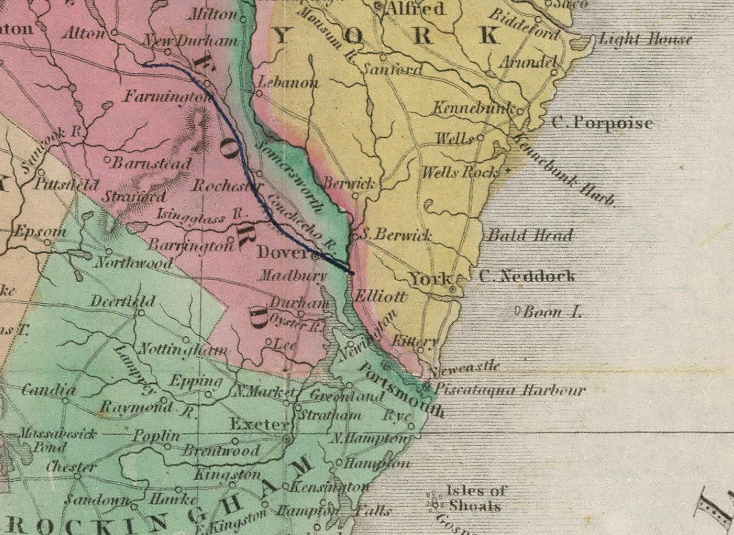

Caption: The Thompson’s point of 1649 no longer exists but was somewhere near the word “Elliott” on the map, on the Maine side of the Piscataqua. Map from the David Rumsey Collection: Link

They had taken on the lease of Thompson’s Point from Sir Ferdinando Gorges by 1647 after his first tenant, Francis Williams, left for Barbados in 1644, leaving Gorges without a renter.[3]

Edward and Richard Waldren, both of Dover, were already engaged in furnishing masts to English shipbuilders and they wanted to expand.[4] They took on the Thompson’s Point lease and started cutting trees. Before long the inhabitants of Piscataqua brought suit against them for removing the lumber from the land they had only rented. Their lease had been granted by a court and sanctioned by Williams, though it is unclear who had the authority to grant permission for logging. Apparently, Edward and Richard’s neighbors thought the lease did not include removing trees. Also at issue was the fact that the boundary between Dover and Eliot/Kittery was not solidified until 1654. The tree removal could have been seen as Dover men encroaching on presumed Kittery territory.

Whatever the root cause, the first shot was fired in June of 1647 when the “Inhabitants of the Pascataquack River (one of the Piscataqua’s many spellings) sued Edward and Richard for the “selling of timber upon the land they are tenants unto.”[5] At this point in New England there were a lot of trees. Cutting a few down, or even clear-cutting Thompson’s Point would not have made a dent in the tree supply. So, what made these trees worth fighting over?

They were particularly valuable. They were being used as masts for English navy and merchant ships. For almost a century, England’s masts had been supplied by the Baltic countries and Norway.[6] The problem was the trees were not big enough in circumference so multiple trees were banded together to make a single mast. The towering white pines of New England were discovered, some with a diameter of over forty inches, and they became the ideal for a first-rate ship of the line, and a lucrative export, in this case for the Dover men.

Four months later, in October of the same year, Edward and Richard were back in court.[7] The record states they had been “attached by their mastes to be responsall to answer what shalbe alleged against them at the generall Court to be helde for this province the 27th of June next.” Being attached by their masts isn’t a physical description, but a legal one. It was a proceeding by which a defendant’s property was taken into custody and held for later payment in case a judgement was found in the plaintiff’s favor. Edward and Richard were probably none too pleased to have their mast-sized trees confiscated, to say the least.

So, what happened next in the Thompson’s Point kerfuffle? Who won the court battle? Did Edward and Richard get their trees back? We have no idea. Like many of the legal battles in the colonial courts it appears the disagreement was resolved outside of court or the paper which had the final judgement is now lost.[8]

Starbuck-Nutter Sawmills

The year 1649 brought in another new business venture for Edward. On the 27th of December 1647, Edward Starbuck and Hatevil Nutter (named as Elder Starbuck and Elder Nutter in the town book) applied to the Selectmen of Dover for permission to build a sawmill on the Lamprey River, which emptied into the Great Bay across from Dover.[9] On the 11th of September 1649 the agreement was finalized and both men were given permission to build sawmills, Edward on the south side of the lower falls and Hatevil Nutter on the north side, near other land he had been granted. There is nothing more in the town records stating whether or not Edward’s sawmill was actually built, but what can be seen from these sources is that Edward had the skills to build a sawmill and make his living as a lumberman, skills which he likely learned back in England in watery Starbucky Territory.

[1] Maine Historical Society, Province and Court Records of Maine, (Portland, Maine: The Southworth Press, 1928), Vol. 1, pages 42, 108-109, 112, 124; digital images, Family Search (www. familysearch.org : accessed 3 March 2022).

[2] Wilbur Daniel Spencer, Pioneers on Maine Rivers with lists to 1651 (Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1973), 109.

[3] Shades of Medieval England appeared in the lease because the land was to be held by free and common socage and was exempt from Knight’s service, though subject to a small annual rental charge. Breaking that down, free socage was tenure based on non-military service (aka Knight’s service), in return for the use of the land. What was not defined was exactly what “use” meant. That could have been defined in the lease or by custom, meaning the land could be leased for agricultural purposes, as a fishing camp, or perhaps the natural resources could be harvested.

[4] Spencer, Pioneers on Maine Rivers with lists to 1651, 110.

[5] York, Maine, Record of the Courts Book 1 1636-1652: 102, Edward Starbuck, 1647; FHL DGS 5,654,540, item 1; digital image 113/208, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : 11 May 2022).

[6] William R. Carlton, “New England Masts and the King’s Navy,” The New England Quarterly 12, no. 1 (March 1939): p. 4-5, https://doi.org/10.2307/359972; digital image, JSTOR (www.jstor.org : accessed 8 December 2022).

[7] York, Maine, Record of the Courts Book 1 1636-1652: 114, Edward Starbuck, 1647; FHL DGS 5,654,540, item 1; digital image 125/208, Family Search (www.familysearch.org : accessed 11 May 2022). Transcription from FHL DGS 5,654,542 image 135/706.

[8] There is no entry for Edward in the court records in June of 1648 or any other time in relation to this suit. The original handwritten book for the York court records from 1636-1652 is numbered sequentially through page 32, but after that the numbering disappears. Too few entries are dated to determine whether much, if anything, is missing from the original record. The other detail is that the Thompson Point House, having been in the possession of Dover residents, was taxed by Dover in 1648 without specifying the owners or renters, a clear indication it was seen as being under the authority of Dover, which lay across the Piscataqua. By 1649 it was again taxed by Kittery.

[9] Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 40, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E. Jenks, State printer, 1867), 124-125; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 3 March 2022).