A GUIDE TO MANORS by Celia Renshaw

Manors and Hundreds

In 1066, William of Normandy invaded Britain and promptly adopted the civil and geographical jurisdiction of England which the Anglo-Saxons and Norsemen had set up, composed of Manors and Hundreds (or Wapentakes)[1]. The Normans fused this with their own feudal system in which the monarch owned all land, kept a lot of it and granted the rest to their loyal nobles in return for military service, and also to the Church.

This manorial system remained in place for many centuries, evolving and gradually weakening over time, and only brought to a final end in the 1920s[2]. Because it lasted so long, its workings and records vary hugely, and to our modern senses are complicated and difficult. But the records the system produced can be vital to genealogical research in England, especially before parish registers began (1530s-50s) and for another couple of centuries after that as well.

At its simplest, the system divided up the whole of England into small chunks called ‘manors’, each held and ruled over by a ‘Lord of the manor’ and overseen collectively in groups called ‘Hundreds’ or ‘Wapentakes’.

Though manors varied in size, many consisted of a village with its surrounding land, waterways, woods and waste. There was usually a large house within the manor (a capital messuage) where the Lord would live or stay.

Every manor had a ‘manor court’ by which the Lord or their most senior servants (steward, deputy steward, bailiff) oversaw local affairs.

Each Hundred was composed of a number of local manors, ruled over collectively by a Hundred Court with responsibility for taxation, laws and keeping the peace. Local custom and practice determined how often these courts met: manor courts might be held every three weeks or only a couple of times a year, while Hundred courts traditionally met every month, reducing in importance as Sheriffs and their county-level administration took over these responsibilities.

Land-holding in the manorial system

Modern Brits and researchers abroad can find it hard to grasp that, at root, British land is all still owned by just a single individual at any one time: the monarch, or rather the monarch’s legal embodiment, The Crown. This has barely any practical relevance today in property business but it matters for family researchers – to understand the language and implications of land-holding records of earlier times.

Thanks to the Norman conquest of our country, with William I grasping ‘ownership’ of every scrap of our land, everyone else’s property-holding has since then been a form of tenure, not ownership, ie. as freeholdings or as leaseholdings of different types, most commonly copyholds.

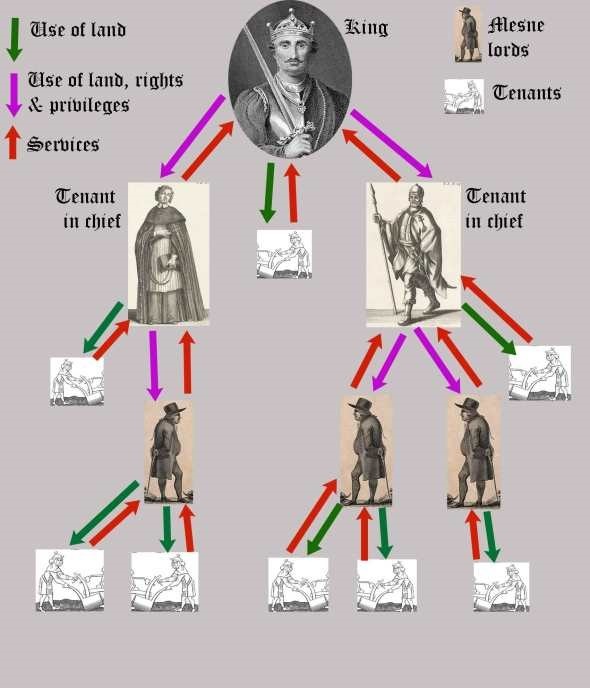

Until the manorial system disappeared, there was a hierarchy of land-holding. The Crown handed out large chunks of land to nobles and knights in return for military service, goods or money, and to the Church, while retaining huge amounts of land for itself, as it still does. The nobles, knights and Church officials or bodies holding land from the Crown were termed tenants-in-chief. The Crown could at any time snatch back the land granted to tenants-in-chief (and often did) at which point all tenants of said lands suddenly became Crown tenants, like it or not.

Tenants-in-chief usually leased out all or part of their holdings to a second level of tenants (usually minor aristocracy or gentry, people sufficiently well-off not to have to work for a living), who often leased out to a third level, and so on.

Freeholders

For reasons of history, some tenants in this hierarchy were freeholders, meaning that they could convey and acquire land and premises without the Lord’s permission and were not subject to most manor customs. They usually paid only a token rent to the Lord, eg. a few pence, a peppercorn or a rose. However, they were still required to pay suit of court ie. to attend court and swear fealty (loyalty) to the Lord, or pay a penalty if they didn’t. They also took their turn in some manorial duties, such as jury members (chosen at each court session) and constables (elected annually). There were often only a few freeholders in a manor, sometimes none, and usually they were the wealthier residents, though not always.

In formerly Viking-held lands under the Danelaw, from 1066 onwards some land-holders were termed sokeholders or sokemen and they were even freer than freeholders, essentially independent of all manor customs and duties except loyalty to the Lord. As time progressed, they were subsumed into the category of freeholders.

As a result of this level of independence, manorial and property records for freeholders and sokemen can be frustratingly few and far between.

Copyholders

Tenants who were not freeholders were leaseholders under a rich variety of formats, including copyhold, customary tenancy, tenancy at will, tenancy for lives, bondhold, tenancy by inheritance and more. Traditionally, when few were literate, most people were tenants “by the rod” so-called because they accepted a token such as a rod of wood to indicate their admission to a tenancy, which was handed back to the Lord when that tenant died or ceased the tenancy. Later, it became more common for tenants to be given a copy of their admission to the tenancy, taken from the court records, and so were termed copyholders. Tenants who leased “by the rod” were termed customary tenants. Most manorial leasehold tenants came to be known as copyholders – it’s important to note that people of all social classes could be leaseholders of lands in a manor and many held a mix of free and leaseholds.

But whatever the format of their tenure, they all held their land and property by permission of the Lord of the Manor and could only convey or acquire it via a system of Surrender and Admission in the Lord’s manor courts. The plus side of this for genealogists is the detailed record kept of tenants and leasehold land conveyances in Court Rolls and Minute Books.

Be specially aware: The fact that an individual (of any class) was either a freeholder or a lease/copyholder in a manor does not mean they definitely resided there: ‘holding’ land or buildings was not automatically the same as ‘living’ on the tenured land or in their messuages and tenements. Wealthy people often held many whole manors, depending on stewards to manage them, plus holdings in other manors around the country. Sometimes such a collection of holdings was a called a fee (eg. Duffield Fee) or an honour (eg. Peveril Honour). Sometimes, a manor or fee was shared between two or more Lords. Tenants often lived on one holding in their manor but held other premises there and in nearby manors as well, used mainly for crops or animals, or as a way to deploy cash savings or gain an asset for security on loans and mortgages (banks were non-existent to most folk until the late 18th and early 19th centuries).

Court Baron and Court Leet

Two types of Court were held for each manor (or fee), often together at one time. Like everything else about manors, Court practice varied over time, between local custom and practice and the preferences of their Lords and stewards.

However, in the broadest terms, the Court Baron and Court Leet (often also called View of Frankpledge) between them maintained manorial customs and practice, took oaths of loyalty, elected manor officials, charged fines for rule-breakers, dealt with disputes (including small debts), and handled and recorded the surrender and admission of leasehold lands. Each Court called or elected juries to consider and resolve disputes and present tenants’ issues for Court consideraton. The Court Baron jury (usually freeholders) was termed the homage. The Court Leet juries were usually of customary tenants and copyholders.

In some cases, the two Courts were held at different times: Courts Baron every three weeks, evolving to only once or twice a year, Courts Leet less often, sometimes just annually, and eventually, in many cases, the two Courts were held together, eliminating the distinction between Baron and Leet. The main importance of the Courts to family history is the Rolls or Books recording Minutes of proceedings, along with any rentals, surveys, maps and boundary-recording by Lords and Stewards.

Locations of manorial records

Other than the Crown’s, manors throughout time were held and conveyed privately, Lord to succeeding Lord, so their records, where they have survived, are still private, unless acquired at some point by state bodies such as County Record Offices or the National Archives. Far too often for comfort, a manor’s records have simply disappeared over time. Attention to the recording and preservation of Court business was entirely individual to each Lord, depending on their or their stewards’ inclinations, and the times they were living in.

When we consider that manor records have been kept over almost a thousand years, since the earliest Medieval period through to the 20th century, any survival seems remarkable. The easiest first step to find records for a specific manor or parish is to check the Manorial Documents Register (MDR) kept at the National Archives (TNA), now updated, digitised and searchable: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/manor-search.

However, that database is not comprehensive because manor records can remain unidentified, especially when privately held, or scattered among family and estate papers that are not fully catalogued – and many archives have not fully catalogued their holdings, let alone fully digitising them for online access. So do not lose hope if you find little at the MDR, keep digging.

Latin and handwriting

Until 1733, Latin was the official legal language of England, so all manorial business until that date was conducted in Latin (apart from one merciful period during the post-Civil War, republican Commonwealth (1650s) when English was the legal language. So, when looking beyond 1733, Latin and ‘spider’s leg’ handwriting with many abbreviations together present a major deterrent for many researchers. However, there is a stunning consistency over a thousand years in the usual wording of manor records, standard formulas that persisted until the 20th century. So, from manor records in English from 1733 we gain effective cribs for much of the earlier Latin. Also, the standard manorial terms and language, strange at first, can be picked up and understood using a good Glossary and with some practice.

Help and guidance

There is no doubt that manor records can be daunting at first sight, but they can also be extraordinarily helpful to family research, with insights into our ancestors lives we seldom gain in other sources. Here are some suggestions for websites and publications that can help you along:

Nottingham University Introduction to Manor Records, with Glossary https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/manorial/introduction.aspx

National Archives Guide : Manors & manorial records

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/manors/

Wikipedia – Manor Courts & Courts Baron: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manorial_court

Wikipedia – Courts Leet:

- Manorial Records (a McLoughlin Guide), short and sweet booklet by Eve McLoughlin

- Latin for Local & Family Historians, by Denis Stuart (Phillimores, 2000-2012)

- Paleography for Family & Local Historians, by Hilary Marshall (Phillimores, 2004-2010)

And finally, the Christianity factor

Christianity first came to the British Isles in or about 597 AD. It has a long and chequered history here, but for genealogical purposes, it’s most important to appreciate that the changing Christian geography, of parishes, deaneries, archdeaconries, dioceses and provinces, existed and intertwined simultaneously with the manorial. For many centuries, English people faced at least two sets of rights, laws and regulations overseen by two national systems – the manorial and ecclesiastical – and there were additional legal and administrative layers too, at local, county, regional and national levels. Sounds like a serious burden to ordinary folk in the past, but the benefit to us researchers today: all of these systems kept records!

[1] Note that the history of manors, feudalism and landholding in Wales, Scotland, Ireland and other parts of the British Isles was different to that in England.

[2] The 1922 Law of Property Act brought to an end the last meaningful function of manorial courts through the abolition of the form of land tenure known as ‘copyhold’.