No marriage record was found in England or New England which could be positively identified as Edward’s. Marriage records for an Edward, which predated his immigration to Dover, were found near Edward’s English origin but none were to a lady named Katherine. There is no doubt he had a wife named Katherine when he lived in Dover and on Nantucket. Beginning with a deed in 1653, three original records identified Katherine as Edward’s wife. The deeds are the only original records found thus far which include her given name. As with most records made on a woman after her marriage, no mention was made of her maiden name.

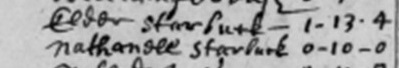

| Date | Location | Transaction |

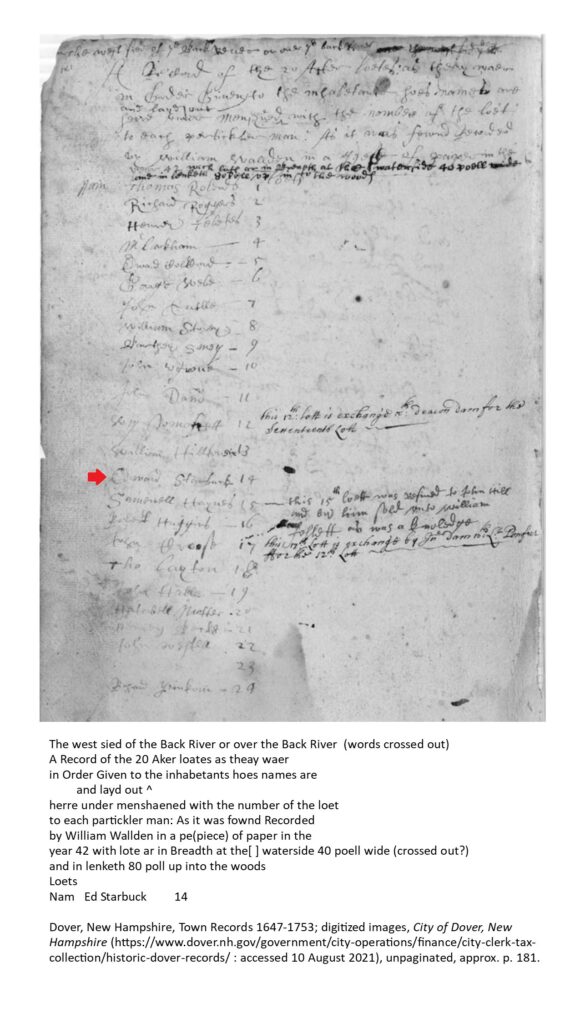

| 20 Jul 1653[1] | Dover (in Rockingham County Deeds) | Edward & Kathren sold ½ Edward’s grant of Cochecho upper falls to Peter Coffyn p. 1 & 2 |

| 6 Mar 1659/60[2] | Dover (in Rockingham County Deeds) | Edward & Kathren sold land to Peter Coffin |

| 19 June 1678[3] | Dover (in Rockingham County Deeds) | Edward & Katherine sold land to Peter Coffin (p. 1 & 2) |

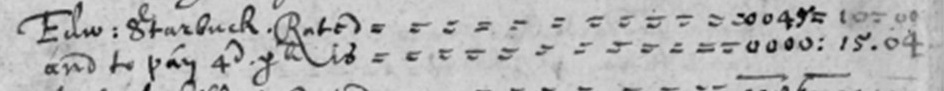

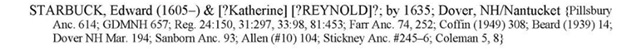

Despite the lack of a marriage record, Katherine has been identified with the surname Reynolds in several compiled sources, sometimes with the addition, “of Wales.” Clarence A. Torrey listed many of the histories in his New England Marriages to 1700.[4]

Of the nine books and four issues of The Register Torrey used (all printed between 1870 and 1988), each identified Edward’s wife as Katherine Reynolds but without an original source to back their statements up.[5]

Continue reading “Edward Starbuck and Katherine Reynolds”