Is it possible to give the same land away twice? Is it legal? Usually, the answer to those questions is a resounding, “NO!” But in the case of land apportioned to Edward Starbuck in colonial Dover the quick answer is, “Yes, he did.” But the real question is why and how did he do that? To find a reason, we must study Edward’s land grants in the Dover town records and Rockingham County deeds.

Edward Starbuck’s Back River Land

This is the timeline of the land Edward Starbuck received along the Back River which flowed on the west side of Dover Neck:

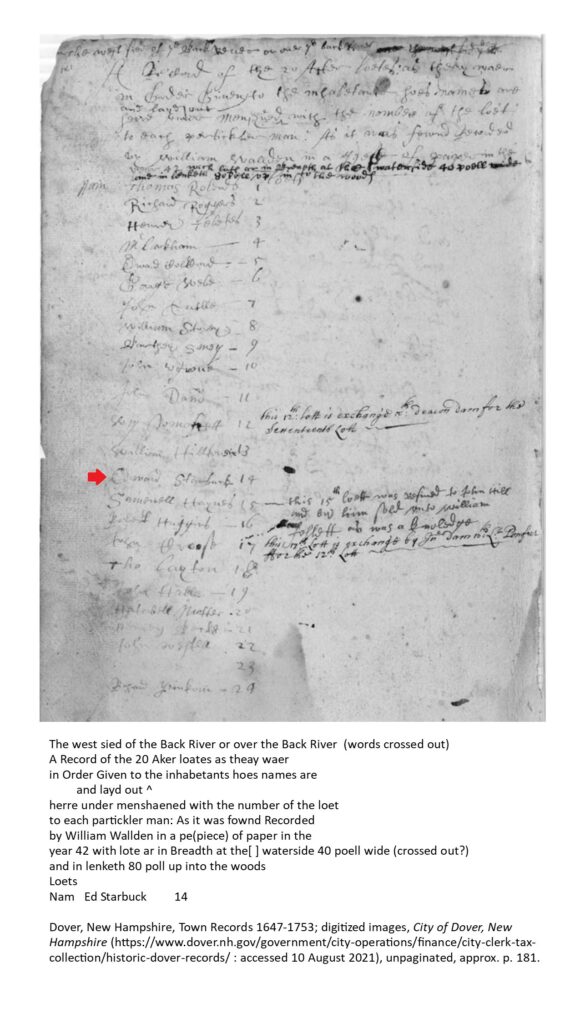

- 1642-Edward Starbuck received 20 acres on the Back River (entered in the town books at some point after 1647 when they restarted after the early records were lost)[1]

- 1652-The twenty acres were still in Edward’s possession (entered in the town books in the 1690s)[2]

- 1652-1662-Edward Starbuck gave Joseph Austin the Back River land during this period (no record of the event was placed in the town records until a later one which implied the action)[3]

- 1663-Joseph Austin’s probate inventory includes his Back River property[4]

- 1664-Edward Starbuck regifted the Back River land to Humphrey Varney (recorded in Dover town records, and in Rockingham deeds in 1699)[5]

- 1696-Humphrey Varney sold the land he received as a gift to William Blackstone (recorded 1699)[6]

Other important facts to know are:

- Joseph Austin married Sarah Starbuck, Edward’s oldest daughter about 1649[7]

- After Joseph’s death in 1662, Sarah married Humphrey Varney 2 March 1664[8]

- Although Joseph Austin’s probate process was started in 1663, nothing else was done or recorded until 1680 when Peter Coffin requested permission to complete it[9]

- Some of Joseph Austin’s land was mentioned in the Dover town records as being in possession of his son, Thomas in 1696, and indication the probate was complete, or nearly complete[10]

There are difficulties in getting the full picture of Dover events, especially with the loss of the earliest town records. Later records are not in chronological order. There are also missing records which can be seen by transactions referenced in later years, which do not appear in the earlier records. These factor in uncertainty. Added to that, the colonists were figuring out property laws and customs for themselves. Land was handled differently in the colonies than it was in England.

How the Colonists Viewed Land Ownership

From Belnap’s History of New Hampshire:[11]

“By this deed, the English inhabitants with these limits obtained a right to the soil from the original proprietors, more valuable in a moral view, than the grants of any European prince could convey. If we smile at the arrogance of a Roman Pontiff in assuming to divide the whole new world between the Spaniards and Portuguese, with what consistency can we admit the right of a king of England to parcel out America to his subjects when he had neither purchased or conquered it, nor could pretend any other title than that some of his subjects were the first Europeans who discovered it whilst it was in possession of its native lords? The only validity which such grants could have in the eye of reason was that the grantees had from their prince a permission to negotiate with the possessors for the purchase of the soil thereupon a power of jurisdiction subordinate to his crown.”

Belnap states how the colonists viewed their land. Whether they got it from the Native Americans by purchase, treaty, or some other means, they felt they were the true owners and owed nothing to the crown for their acquisition. But despite their near universal colonial belief the land they acquired was theirs, various colonies had different laws for property including widows and their dower rights.[12] Massachusetts chose to restrict those rights more than England did, but the Piscataqua Plantation towns were not Massachusetts despite being under the Bay’s governance. As part of the deal for Dover and surrounding towns moving under Massachusetts Bay’s control, the towns insisted on having less puritanical laws and customs.[13]

Edward Gives His Back River Land to Joseph Austin, and then to Humphrey Varney

The central question among all this remains, how and why did Edward Starbuck give his Back River land twice, and was that legal? What really happened to the land between 1663 and 1664?

Unfortunately, those gaps in the Dover records make it difficult to tell if Edward purchased the land back from Joseph prior to his death or from Sarah. If he got it from Joseph, it shouldn’t have been in Joseph Austin’s probate inventory. It’s possible he bought it back to help Sarah with finances, but there’s no record of that. As a widow, Sarah may have been able to sell property that was hers by dower right, but Joseph Austin’s probate was not settled by 1664. There was no partition of property given to Sarah, let alone a specific one with the Back River land. It’s highly unlikely Edward bought the land from either Joseph Austin prior to his death or from Sarah, if she was even allowed to sell it.

The land may have been on loan from Edward Starbuck to Joseph Austin for his use for as long as he was married to Sarah. But if that was the case, those conducting Joseph Austin’s probate inventory should not have listed the land amongst Joseph’s real estate holdings. It’s unlikely the inventory men, all long-time associates of both Edward Starbuck and Joseph Austin, got Joseph’s ownership wrong.[14] While the regifting might be chalked up to simply “doing things differently back then,” there are some other intriguing possibilities.

Did Humphrey Varney Get the Back River Land Legally?

It’s likely Humphrey Varney’s desire to sell the Back River property to William Blackstone triggered a need for proof he had clear title to the land. He may have had the document signed by Edward in his possession since 1664, and until the time of the sale, there was no need to use it. With William Pomfrett witness to the 1664 event and the town recorder, he would have been in a good position to challenge Varney’s ownership, but he didn’t. Although Edward moved to Nantucket by 1661, he could have easily sent a document verifying his gift of land to Humphrey Varney or written it up on a trip back to Dover in 1664, perhaps for the occasion of Sarah’s marriage to Humphrey.

It’s remotely possible Humphrey Varney forged his deed or had one of his brothers-in-law, Nathaniel Starbuck or Peter Coffin write it up. With Edward deceased by 1696, he could not object to Varney claiming ownership of the land or help him acquire it. However, Sarah (who was alive in 1696) made no objection to Humphrey selling the land. Additionally, no one in Dover objected. Occasionally town records document land disputes, but there’s none for the Back River property. The logical conclusion is that Edward wrote the document and Humphrey Varney had it entered into the town and property records in the 1690s.

Why Might Edward Have Gifted the Back River Land Again?

All these details circle back to the basic question of why Edward wrote the 1664 note to give Joseph Austin’s Back River land to Humphrey Varney. With Joseph Austin’s probate unsettled when Sarah remarried in in 1664, Edward likely wanted to make sure Humphrey got some land as a gift for marrying his daughter and taking care of his Austin grandchildren. Edward had sold or given away all his land in Dover, but he might have considered this parcel his to give again whether it was “strictly legal” or not.

It’s apparent Edward legitimately believed he could take the land back and give it again. He may have seen himself as his grandchildren’s guardian though no one recorded that status. Even though Edward was on Nantucket at in the 1660s, the two towns were not that far apart by ship, and he could have returned to Dover occasionally, though he didn’t have to be in Dover to act as a guardian. The town may have recognized his right to use that land for the benefit of his grandchildren who were Joseph’s heirs. When Sarah married Humphrey, Edward may felt it was his right to give the land to Humphrey for the upkeep of his daughter and grandchildren.

In Conclusion

From the records currently available to us, we can’t know how or why Edward Starbuck conveyed the same property twice, the best we can do is make educated guesses. But this we do know: whatever Edward’s reasons were, no-one objected and it benefited his daughter Sarah’s spouses and family, as was needed and deserved.

We also know it’s unique in the 17th century land conveyances of New England – unless other records of double-gifting pop up one day.

For a fuller version of events click here.

[1] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, New Hampshire (https://www.dover.nh.gov/government/city-operations/finance/city-clerk-tax-collection/historic-dover-records/ : accessed 10 August 2021), unpaginated, approx. p. 181.

[2] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, NH (https://www.dover.nh.gov/government/city-operations/finance/city-clerk-tax-collection/historic-dover-records/ : accessed 10 August 2021), 117.

[3] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, NH (https://www.dover.nh.gov/government/city-operations/finance/city-clerk-tax-collection/historic-dover-records/ : accessed 10 August 2021), 114.

[4] “New Hampshire, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1643-1982,” database with images, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com : accessed 25 July 2022), Joseph Austin p. 1, 2, 3.

[5] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, NH (https://www.dover.nh.gov/government/city-operations/finance/city-clerk-tax-collection/historic-dover-records/ : accessed 10 August 2021), 114.

“Rockingham County, NH deeds,” database, Ava (www.ava.fidlar.com : accessed 9 Jun 2022), Edward Starbuck, 1696-05-02.

[6] “Rockingham County, NH deeds,” database, Ava (www.ava.fidlar.com : accessed 9 Jun 2022), Humphrey Varney, 1696-05-02.

[7] “Clarence A. Torrey, New England Marriages to 1700,” database with images, American Ancestors (www.americanancestors.org : accessed 25 July 2022), Joseph Austin. This source states, “by October 1649.”

Deborah, the oldest child of Joseph and Sarah (Starbuck) Austin had her first child 1 June 1669 in Nantucket (VR). For her to marry at an average age in approximately 1668, she was born about 1647-49. John Ham’s Dover, New Hampshire Marriages 1623-1823 stated Deborah’s marriage took place in 1668. The Nantucket vital records and Ham’s book were the two best sources, in addition to Torrey, for estimating the marriage of Joseph Austin and Sarah Starbuck.

[8] “Clarence A. Torrey, New England Marriages to 1700,” database with images, American Ancestors (www.americanancestors.org : accessed 25 July 2022), Humphrey Varney. This source states, “2 March 1664.”

[9] Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 31, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E Jenks, state printer, 1867), 56-57; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 25 July 2022), Joseph Austin, 1663 p. 1-2.

“New Hampshire, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1643-1982,” database with images, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com : accessed 25 July 2022), Joseph Austin p. 1, 2, 3.

Nathaniel Bouton, editor, New Hampshire State Papers vol 40, (Concord, New Hampshire: George E Jenks, state printer, 1867), 359; digital images, New Hampshire Secretary of State (www.sos.nh.gov : accessed 2 Jan 2023), Joseph Austin admin granted to Peter Coffin.

[10] Dover, New Hampshire, Town Records 1647-1753; digitized images, City of Dover, NH (https://www.dover.nh.gov/government/city-operations/finance/city-clerk-tax-collection/historic-dover-records/ : accessed 10 August 2021), 117.

[11] Rev. Jeremy Belnap, The History of New Hampshire, Vol. 1 (Dover, New Hampshire: S. C. Stevens & Ela & Wadleigh, 1831), 8.

[12] Marylynn Salmon, Women and the Law of Property in Early America (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 6-8.

[13] George Wadleigh, Notable Events in the History of Dover, N. H. (Dover, NH: No printer named, 1913), 18-22.

[14] Those signing off on the inventory were Hatevil Nutter who had known Edward since 1638, and long-time residents John and Ralph Hall. See “New Hampshire, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1643-1982,” database with images, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com : accessed 25 July 2022), Joseph Austin p. 2.