1670 CHANCERY CASE : KENDALL vs KENDALL[1]

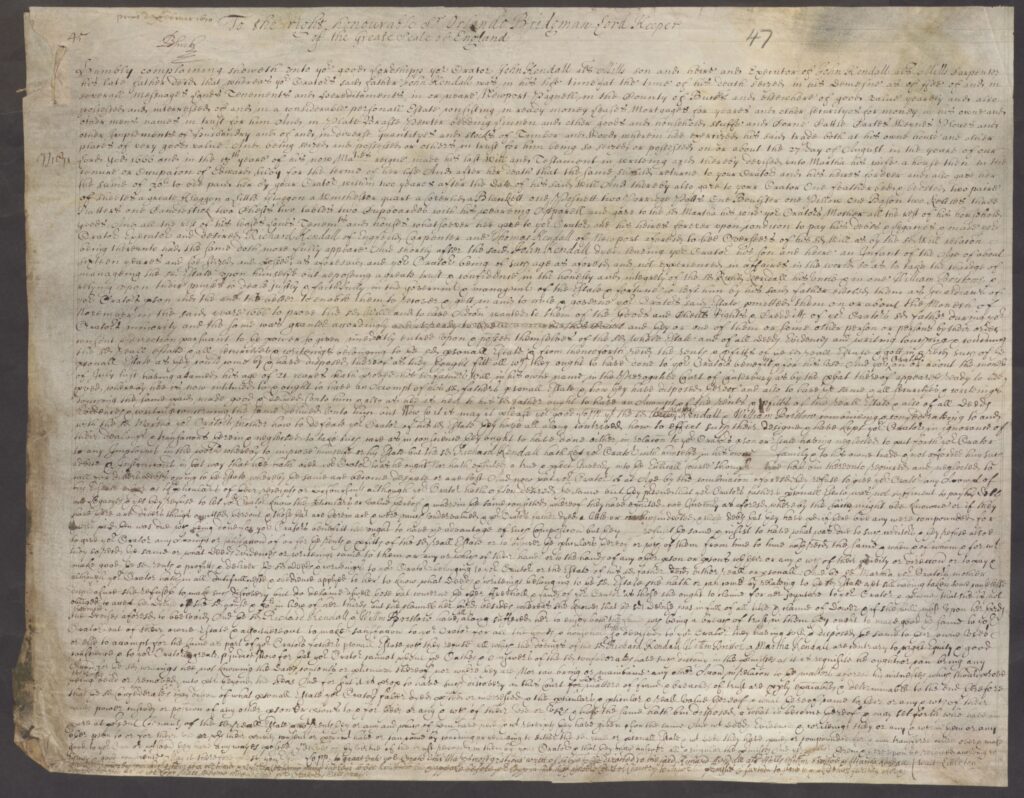

TNA ref: C 8/172/47

Abstract of Bill and Answer analyzed by Keri-Lynn & Celia Renshaw, 8 Aug 2023, from images supplied by TNA to Keri-Lynn[2]

The Charge

Primo day of Februarie 1670

To the right honourable Sr Orlando Bridgman Lord Keeper of the Great Seale of England

First sheet: the submission of John Kendall alias Mills (referred to by us, for clarity, as John Jr. and later as Aberford John), the only child of John Kendall alias Mills Sr. and an unknown first wife. John Sr. died in the plague at Newport Pagnell in 1666, after marrying a second time, to widow Martha Mitchell. John Sr. was the son of Sherington Rafe, making him the brother of Thomas and Francis in New England and of Richard in Enfield.

John Jr., the complainant in this Chancery case, referred to himself throughout the charge as ‘Your Orator’ (standard form of address to the legal authority) – for simplicity ‘he’ or ‘John Jr.’ has been used instead.

John described himself as John Kendall alias Mills, the son, heir and Executor of John Kendall alias Mills, carpenter, his late father. John stated his father possessed several freehold messuages, lands, tenements & hereditaments in or near Newport Pagnell & elsewhere of good value during his lifetime and at the time of his death, and that he had a considerable personal estate consisting of ready money, leases, mortgages & other securities in his own name and in other men’s names in trust for him. His father’s household goods included plate, brass, pewter, bedding, linen, etc plus corn, cattle, carts, wains, ploughs and other husbandry implements, plus stocks of valuable timber and wood used in his carpentry trade both at his own house and other places.[3]

John’s father died on or about the 27 August 1666 after making his last will and testament devising to his wife, Martha, a house then in the tenure of Edward Sibly for the term of her life. Afterwards, it was to return to John Jr.’s possession.[4] John Sr. also gave Martha a sum of £30 to be paid to her by John Jr. within two years of the date of the will.

John Jr. listed the assorted household goods that his father bequeathed to him in detail (exactly as written in the will), while the remainder of the household goods were left to his stepmother, Martha.[5] John Sr.’s remaining properties and assets were left to his son John Jr., on condition he paid his father’s debts and legacies. John Jr. was appointed his father’s Executor, with Richard Kendall carpenter of Enfield (John Sr.’s brother) and Thomas Kendall (relationship not determined) of Newport Pagnell as Overseers.

When John Sr. died, his son John Jr. was sixteen years old (termed an ‘Infant’ in the statement). He likely did not feel sufficiently experienced in the ways of the world to take on the responsibilities bequeathed to him as executor.[6] Instead, he placed full trust in the honesty of his uncle, Richard Kendall, and one William Bristowe to manage the estate left to him, electing them his guardians during his minority. In November 1666, they proved his father’s will. With temporary administration granted to them over John Sr.’s estate, they officially entered the premises and took possession of all deeds, evidences, and writings that related to them, and from then on received all rents and profits out of the real estate on behalf of their ward.

All this should have been done for their ward’s benefit. However, by July 1669 John Jr. reached the age of twenty-one, and proved his father’s will in his own right at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury. He was therefore entitled to receive a full accounting from the guardians of his father’s personal estate and how they had disposed of it. They were obliged to hand over all writings, accounts, and evidences, and to produce an inventory. John Jr. stated his uncle Richard, and William Bristowe were in “confederation” with his mother (stepmother) Martha in their endeavour to prevent him attaining his estate by right, keeping him in ignorance of their dealings, and that they failed to deliver his entitlement.

John further stated his guardians and Martha told him there wasn’t enough personal estate left to pay his father’s debts and legacies, but they refused to provide evidence of this. John believed his father was only a little indebted and in fact had debts owed him, which were not claimed, and that it was too late to obtain them.

He stated he respectfully asked his stepmother Martha to tell him what writings and evidences she possessed but she had taken some “causeless displeasure” and refused to comply, and instead “do detaine as well those that concerne the other freehold & landsof your Orator as those she ought to claime for her owne joynture.” He reported Martha stated she was not obliged to accept the house and £30 bequeathed by John Sr. as her thirds and instead claims her thirds in addition to the house and money, even though she knew that bequest was her entitlement in full, which would be void if she challenged it.[7]

John also stated Richard and William have “all along” allowed her to enjoy “both the Lands,” a breach of trust by them that they ought to make good to John Jr. from their own estates.[8] They should also compensate him for the household goods he was bequeathed that they sold and disposed of for their own uses. In other words, all the doings of Richard, William and Martha are “contrary to right, equity & good conscience and of great prejudice to him,” John Jr.

The confederates, as John calls them, insisted they did not have any of the writings and particulars necessary to draw up accounts and the information he requested, nor did they know where those were – “the witnesses that should prove the same being dead or removed into parts beyond the seas.”

The final part of the submission, in lengthy legalese, asked his Lordship to request from His Majesty a subpoena to be served on “the confederates” to appear before the Court of Chancery and to supply all the detailed information, writings, evidences and information that he, John Jr., had a right to receive.

_______________________________________________

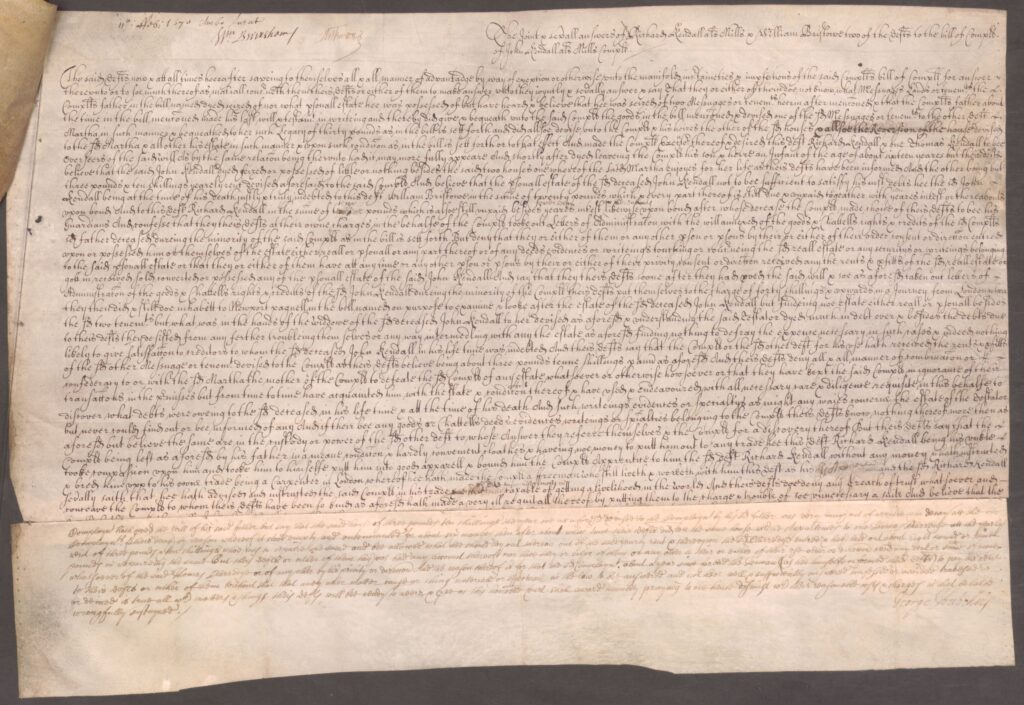

The rebuttal

11th Feb: 1670. Ambo Jurat

Wm Beirsham?. ?C Wilkinson.

The Joint & sevrall answers of Richard Kendall als Mills & William Bristowe two of the defendants to the bill of Complaint of John Kendall als Mills Complainant.

Richard (speaking in the plural we) began their submission with a legal protective statement and denigration of the quality of John Jr.’s complaint, then they swung straight into denials: they did not know all the messuages, lands or tenements John Sr. possessed and died seized of, nor what personal estate he had when he died, but they had heard and believed he held two messuages, which were left in his will, one to wife Martha for life and the other to son John. They agreed with John Jr.’s description of the will’s contents, including the legacy of £30 to Martha, and appointment of John Jr. as executor, with himself (Richard) and Thomas Kendall as Overseers. They agreed that John Sr. died shortly after making his will, leaving his son and heir John Jr. aged 16. However, they believed John Sr. died “possessed of little or nothing besides the said two houses” (one for Martha for her life, as they “have been informed”) “the other being but three pounds & ten shillings yearely rent devised to the said Complainant.” They believed John Sr.’s personal estate “not to bee sufficient to satisfy his just debts hee the s[ai]d John Kendall being at that time of his death justly & truly indebted to this defendant William Bristowe in the summe of twenty pounds” (still unpaid plus 10 years’ interest owing) plus £10 pounds owing to Richard, also still unpaid plus 4 years’ interest owing.[9]

They agreed John Jr. chose the two of them to be his guardians during his minority and at their own expense they took out letters of administration for the goods & chattells, rights & credits of John Sr.’s estate for the period of John Jr.’s minority. But they denied they or any other person took possession of any part of that estate, real or personal, or of any deeds, evidences or writings for the same. Nor have they received any rents or profits from the real estate or received or sold any of the personal estate. Instead, as soon as they had the letters of administration, they “put themselves to the charge of forty shillings & upward in a Journey from London where they then did & still doe inhabitt to Newport Pagnell… on purpose to examine & looke after the estate of the s[ai]d deceased John Kendall but findeing noe estate either reall or personall besides the two tenements but what was in the hands of the widdowe… & to her devised, and understanding the said testator dyed much in debt over & besides the debts due to us, they desisted from any further troubleing themselves or any way intermedling with any the estate… finding nothing to defray the expence necessary in such cases & indeed nothing likely to give satisfaction to creditors…”

They stated that John Jr., “or the said other defendant for his use,” received the yearly rent of £3 10s from the other messuage inherited by John Jr.[10] They denied any suggestion of connivance with Martha to deny John Jr. his inheritance or that they have kept him in ignorance of their transactions for the premises. Indeed, they always did their best by their ward, explaining at various times what the state of the estate actually was, and in his interest put effort into finding any debts owing to John Sr. in his lifetime, and any evidences of such, but they didn’t find anything. If there were any writings, evidences, household goods or anything else belonging by right to John Jr., they did not know of them.

In fact, with John Jr. being left by his deceased father in a “meane condition & hardly convenient cloathes & haveing noe money to putt him out to any trade hee this defendant Richard Kendall being his unkle tooke compassion upon him and tooke him to himselfe putt him into good apparell & bound him the Complainant Apprentice to him Richard all without any money & hath instructed & bred him upp to his owne trade being a Carpenter in London whereof hee hath made the Complainant a Freeman who still liveth & worketh with him this defendant as his journeyman.” Richard also instructed John Jr. along the way about how to build a livelihood in the world. He denied any breach of trust and they “believe that the Complainant to whom these defendants have been so kind as aforesaid hath made a very ill requitall thereof by putting them to the charge & trouble of soe unnecessary a suite.”

Richard’s answer continued (in different handwriting on a new piece of paper attached along the bottom) that he knew John Jr. had proved his father’s will but that the house bequeathed to him was “very much out of repaire and in decay” at the time of John Sr.’s death, and had therefore stood empty and untenanted for about six months, when they (Richard and William) leased the place to Thomas Clarredge at the yearly rent of £3 10s, which he could use to pay for repairs. Clarredge has since then laid out about £8 or £9 on repairs but they the defendants had not received any account of this, nor any of the rent from Thomas Clarredge for this property, because about a year ago John Jr. forbade the tenant to pay his rent to us (as he, John Jr., told us himself).

They finished by pleading the Court to bring the case, so wrongfully brought against them, to a speedy dismissal.

On the reverse of the defendants’ answer is a thin fold of paper containing about two lines of writing, setting out the same information about the £3 10s house being let to Thomas Claridge but with different wording. It appears this was folded over and the new wording was attached to the main sheet instead.

Analysis

So, who is right, John Jr., or Uncle Richard and William Bristowe? Richard and William mentioned John Sr. died possessed of little or nothing besides the said two houses in poor condition and that he owed debts to William Bristowe which had never been paid. John Jr., on the other hand, believed his father died possessing several freehold messuages in Newport Pagnell & elsewhere of good value and considerable personal estate, with some of that estate in trust. The two descriptions could hardly be farther apart. The truth probably lies somewhere in between. John Jr. wanted to present what he felt was due to him in the best possible light while those who were managing the property for him would prefer to have it undervalued which would negate their responsibility to come up with paperwork and back rents for John Jr.

With no additional documentation for his case, including the court’s final judgement, it is hard to say where the truth lies. The case may have been dropped by John Jr. or continued with further testimony or judgement statements which are lost to time. From where we sit today, there is little, if anything, we can do to determine if John Jr. gave up or if he received money he felt was due to him from his guardians.

Keeping it in perspective

Something to remember is that John Jr. did not claim the two properties were being kept from him. He knew one belonged to him and the other would become his after Martha’s death. John Sr.’s will named no specific bequest to John Jr. of a second house, rather it referred to household items “in the other house,” proof that John Sr. knew he had two houses. This fact is backed up by the documents in the Chancery case where both properties were mentioned, one rented to Thomas Claridge and one where Martha and George Rawbone (probably) lived. John Jr. would have gotten the one property (rented by Claridge) upon his father’s death, but it was delayed by his minority. It came to him when he proved his father’s will again in 1669 or 1670.

In 1670, Martha (along with husband, George Rawbone) held the Old North Bridge property. Martha was entitled to it until her death, and the other one, in an unknown location, went directly to John Jr. in 1670. Proof of that was his receipt of rent directly from Thomas Claridge. However, the second property was decrepit and worth little, and Claridge had apparently been told previously to put the rent towards repairs instead. That would have upset John Jr., discovering there were essentially no funds set aside to come to him.

Given the wording of his claim, John Jr. may have thought there was more to his father’s estate than just those two properties and that his uncle, Richard, and William Bristowe had defrauded him from those extra properties, goods, profits and money (suggested by the wording of his father’s will) and that they also failed to provide an inventory, accounts, and written evidences of any kind. John Jr. had a point, legally. The will’s legalese suggested John Sr. had more assets.

Not knowing specifically what all his father owned, as most sixteen-year-olds would not, John may have had an inflated idea of his father’s possessions. We also do not know if, in fact, John Sr. did have more properties which should have gone to his son. This is the crux of the lawsuit. John Jr. was not trying to kick Martha (and George) out of their home, but rather to retrieve the written documents pertaining to all his father’s estate, the rent money he believed had been paid and control of all other property his father had at the time of his death.

Martha’s Dower Rights

One question some readers might raise is what was Martha’s right to the dower property once she remarried? The best answer to that is it depends. In fact, it depends on a lot of things. Rather than create another post to describe all the possibilities, I will lay out a few facts which would have influenced the amount of control Martha had over the property.

- The property was in a trust, placed there by the 1666 settlement deed John created before he married Martha.[11] This settlement superseded any custom limiting Martha’s dower to only one third of the property as common law in theory allowed.

- There were four types of property law in England at that time (Manorial, Ecclesiastical, Common Law and Equity). Women mostly dealt with common law followed by equity law, but all four types of property law recognized the right of a woman to receive something if she survived her husband.[12] What that something was always varied and changed over time.

- When it came to women and property, people did not attach the same overriding importance to the common law that later centuries did.[13] Also, there was nearly equal access in most places to common, ecclesiastical, manorial, and equity courts to settle questions.

- Few limitations were placed on dower rights or property through wills, and Martha’s case was the norm with no specifications for giving up her right to the property before her death.[14] Unlike the seventeenth century American colonies, it was less common for a widow in England to be required to give up her land upon remarriage or upon a minor heir reaching majority.

- While it is useful to know the laws and conventions that existed in 1670, it is important to realize there were variations on these depending on location and time, and between people of different wealth/class status, and occupation. There is also the fact that not everyone knew property law, and even if they did, our ancestors often did what was reasonable and expedient even if it wasn’t to the exact letter of what the law of that time dictated.

For these reasons, and more, it isn’t possible to state with certainty what law(s) governed dower rights and how typical it was for them to be followed or enforced. No evidence has been found of any action taken against Martha for living on the land after she married George Rawbone, so it’s reasonable to assume the family believed she had that right.

Though we do not have documentary evidence for the outcome of this lawsuit or the judgement that was rendered, it appears John Jr. was able to gain some control over the property he felt was his. The next thing we know about this property comes from a lease John Jr. was able to make in 1673.

Other posts in this series:

1629/30 Robert Markes to Ralph Kendall als Mills

Land of the Kendall alias Mills Family

1654 Deed of Gift from Ralph Kendall alias Mills to his son, John

1666 Deed of Settlement from John Kendall als Mills to his betrothed, Martha Mitchell

1666 Will of John Kendall (alias Mills)

1673/74 John Jr. and the Old North Bridge Property

1681 Lease and Release to Jeremiah Smalridge

[1] The Chancery was the primary court of equity, thus it dealt with fairness and doing justice when a strict adherence to common law was inadequate.

[2] The National Archives of the UK (TNA) Chancery ref. C 8/172/47 (1670), John Kendall als. Mills vs Richard Kendall als Mills, William Bristowe and Martha Kendall.

[3] Most of this wording is an exact copy of wording in John Sr.’s will, but not all of it. The will does not include any mention of “corn, cattle, carts, wains &c,” or “valuable timber and wood at his own house or other places”. Nor does it mention “ready money, leases, mortgages & other securities in his own name & in other men’s names in trust.” So it’s a question: how did he know his father had such assets? Or was it a lawyer planting those phrases to beef up the submission?

[4] This fits with the burial entry in the Newport Pagnell register: William Kendall, Alice Bowry, Mary Bowry, John Ken[dall] and John Burges buried the 30th day (August 1666)

“England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858,” database with images, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed 15 March 2023), John Kendall, 1666.

[5] Martha was not John Jr.’s birth mother, she was his stepmother.

[6] This suggests John Jr. was born about 1650. His unknown birth mother must have died between 1650 and May 1666, probably in a year when the parish registers were poorly kept.

[7] “England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858,” database with images, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed 15 March 2023), John Kendall, 1666. John Sr. clearly outlined Martha’s bequest in his will,

[8] John’s choice of wording suggests he knows there are only two premises at stake, not the vast real estate and assets his introductory paragraphs describe.

[9] Suggesting John Sr. took the loan from Bristowe in 1660 and the other from brother Richard in 1666 not long before he died.

[10] William Bristowe, not Martha, since the word ‘his’ is used

[11] Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire, original deed of settlement DB 111/3, John Kendall als Mills to wife, Martha, and Robert Hootton (1666); Aylesbury Buckinghamshire Record Office.

[12] Amy Louise Erickson, Women & Property in Early Modern England (London, England: Routledge, 1995), 24-25.

[13] Erickson, Women & Property, 30.

[14] Erickson, Women & Property, 166 & 169.