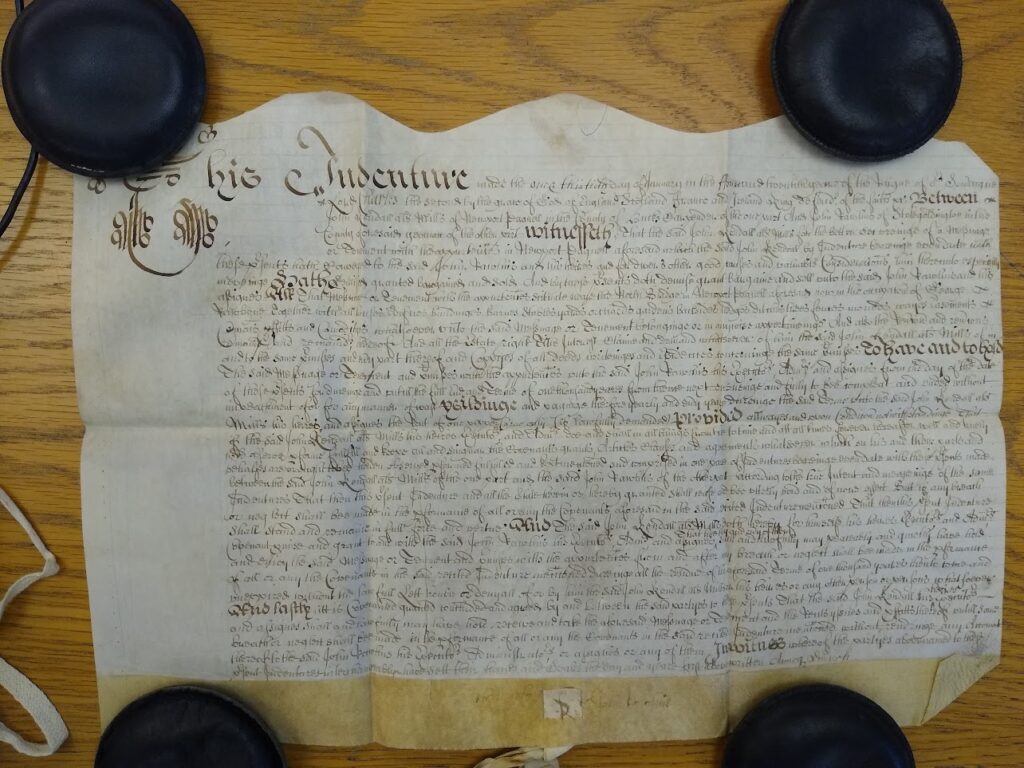

Deed

DC13/3/1/1 (1669-1689) Property on North Bridge – the Ship & Cottages. In 1673, Kendall alias Mills to John Rawlins, messuage in occupation of George Rawbone. Other later deeds in the bundle concern Walter Beaty (Scotch chapman).

Transcription by Keri-Lynn

This Indenture made the one & thirtieth day of January in the Four and twentieth yeare of the Raigne of o[ur] Sovaigne (sovereign) Lord Charles the second by the grace of God of England Scotland France and Ireland King defender of the faith &c. Between John Kendall als Mills of Newport Pagnell in the County of Bucks Carpender of the one part And John Rawlins of Stokegoldington in the County aforesaid yeoman of the other part Witnesseth that the said John Kendall als Mills for the better secureinge of a Messuage or Tenement with the appurtences in Newport Pagnell aforesaid which the said John Kendall by Indenture bearinge even date with these presents hath Conveyed to the said John Rawlins and his heires and for divers other good causes and valuable Considerations him thereunto especially moveinge Hathe Devised granted bargained and Sold And by these presents doth devise grant Bargaine and sell unto the said John Rawlins and his assignes All That messuage or Tenement with the appurtences scituate neare the North Bridge in Newport Pagnell aforesaid now in the occupacon of George Rawbone Together with all houses edifices buildings barnes Stables yards orchards gardens backsides hedges ditches trees fences mounds wayes Easements Commons proffitts and Comodityes whatsoever unto the said Messuage or Tenement belonginge or in anywise appertaineinge And also the reversion and reversions remainder and remainders thereof And all the Estate right Title Interest Claime and demand whatsoever of him the said John Kendall als Mills of in and to the same premisses and evry part thereof and Coppyes of all deeds writeinges and Evidences concerning the same premisses To have and hold The said Messuage

or Tenement and premisses with the appurtences unto the said John Rawlins his Executors Adm[inistrat]ors and assignes from the day of the date of these presents for dureinge and untill the full End and Terme of one thousand yeares from thence next ensueinge and fully to bee compleat and ended without impeachment of or for any manner of wast Yeildinge and payinge therefore yearly and evry yeare dureinge the said Terme unto the said John Kendall als Mills his heires and assignes the Rent of one peppercorne only (if lawfully demanded) Provided allwayes and upon Condicon notwithstandinge That if the said John Kendall als Mills his heires Executors and Adm[inistrat]ors doe and shall in all things from t[im]e to time and att all times forever hereafter well and truely hold observe performe fullfill and keepe all and singular the Covenants grants Articles Clauses and agrements whatsoever which on his and their parts and behalfes are or ought to bee holden observed performed fulfilled and kept menconed and comprised in one pare of Indentures beareing even date with these presents made between the said John Kendall als Mills of the one part and the said John Rawlins of the other part according to the true Intent and meaneinge of the same Indentures That then this present Indenture and all the Estate herein or hereby granted shall cease and bee utterly void and of none effect Butt if any breach or neglect shall bee made in the performance of all or any the Covenants aforesaid in the said recited Indenture menconed That then this present Indenture shall stand and remaine in full force and virtue And The said John Kendall als Mills doth hereby for himself his heires Execuors and Adm[inistrat]ors Covenant promise and grant to and with the said John Rawlins his Executors Adm[inistrat]ors and assignes ^That hee they and any of them^ shall and lawfully may peaceably and quietly have hold and enjoy the said Messuage or Tenement and premisses with the appurtenances from and after any breach or neglect shall bee made in the performance of all or any the Covenants in the said recited Indenture menconed dureinge all the residue of the aforesaid Terme of one thousand yeares then to come and unexpired without the lawfull Lett trouble or denyall of or by him the said John Kendall als Mills or his heires or any other person or persons whatsoever And lastly itt is Covenanted granted concluded and agreed by and between the said partyes to these presents That the said John Kendall his ^heires^ Executors and assignes shall and lawfully may have hold receive and take the aforesaid Messuage or Tenement and the Rents yssues and proffitts thereof until some breach or neglect shall bee made in the performance of all or any the Covenants in the said recited Indenture menconed without rendringe any Accompt thereof to the said John Rawlins his Executors Administrators or assignes or any of them In witness whereof the partyes abovenamed to these present Indentures interchangeably have sett their hands and Seales the day and yeare first above written Anno Dmi…

Signed: the marke of John Rawlins

This is the final agreement made in the Court of our Sovereign Lord the king at West[ ] on the morrow of the Holy Trinity in the twenty ninth year of the Reign of George the Second (1756?) by the grace of God of Great Britain France & Ireland King Defender of the Faith xc. Before John Willes Edward Clive Thomas Birch Henry Bathurst Justices and afterwards in fifteen Days of St. Quarcin in the Thirtieth year of the Reign of the said King George….

A word about title deeds

Confusing is the only way to describe this deed, and that description can apply to many other title deeds. There are several reasons for that, many of them rooted in the history of land use and ownership in England. Celia’s Guide to Manors post explains the historical perspective. Even when individuals owned land, they still owed fealty to a local lord or town, or the crown. Added to that, the concept of land ownership has been in flux for centuries. Then there’s the leases. Historically most properties were rented rather than owned, and there are different types of rental agreements. Leases can also be bequeathed, pending the property owner’s approval.

Topping that off, title deeds were not regulated for a long time. In the American colonies, towns and large landowners parceled their property and sold it or distributed it to those with a residency claim or sufficient funds to buy it. To prove ownership, most wanted their deeds registered. Such records were kept by a government entity, including the colonies, towns, and/or counties, from a very early time. Colonial deeds specified who got what land, which was described by the number of acres, rods, and perches plus where that land was in relation to other owners and the landscape itself. In England in the 1600s, land records were not kept by the government (except when lands were held by the Crown). Rather they were kept in lawyers’ and clerks’ offices and within the family, so their survival is up to those who held them.

Further confusion can result from the various methods of identifying land plots which had been in use for centuries. They were often named (which could change over time), known by the current or a previous owner, and later they were mapped. Going from an open-field system to the more compartmentalized enclosures had its own set of complications. Theoretically, whenever land was transferred, an attempt was likely made to document the change in ownership or occupancy (often called an ‘abstract of title’), but there is no guarantee such documents have survived. Some which did might still be buried in a county or private archive.

Thankfully, a full understanding of title deeds is not needed for them to be useful. We simply must be careful with how we use them. A deed’s most basic components are the names, dates, and places. For family historians, these are the important details because they tell us an individual was alive on a certain date and was in the place an event occurred (the signing of the deed). However, that does not mean the signer ever lived on the land described in a title deed. It means they had an interest in the land and might live on it or might rent it to someone else, who might in turn rent it to yet another individual. Ownership was no guarantee of occupancy. Some deeds have additional details such as a person’s occupation or family names and relationships, which can also be helpful. If a dispute about ownership or inheritance arose, that could generate additional documentation, which we may or may not find.

Words we think we understand get muddled when used in title deeds. The words owned, of, held, occupied (and similar terms) can take on nuanced meanings. Stating someone is the occupier of a property doesn’t guarantee that person physically lived there. It means they were the legal occupier, allowed to hold it by ownership, by legal right, or by rent payment, but not necessarily on that property which could be sub-let to yet another person.[1]

Analysis:

Keeping the uncertainties of title deeds in mind, we can only say this 1673 indenture was drawn up between John Kendall als. Mills (Jr.) and John Rawlins of Stoke Goldington. The indenture appears to be half of a lease and release arrangement but even that is not certain.

Lease and release deeds gained popularity due to most individuals’ willingness to avoid spending more money than necessary. As far back as the 1500s a strategy named livery of seisin (literally delivery of possession) developed.[2] This kept the inheritance of freehold property from public knowledge, which meant one’s feudal superiors were unaware of the transfer and could not charge the relief payment or other allowable fees for inherited land. Livery of seizin employed a strategy which used a large group of people who agreed to hold the land for the inheritor’s use, which avoided documented ownership. It was highly unlikely the entire group would die at once, so there was no relief or inheritance tax due when one or two members of the group passed. This practice was stopped by a 1535 law, but that did not put a stop to efforts to avoid extra payments.

By 1610, a new type of deed was being employed in which the seller of a property would lease land to a prospective buyer ostensibly for one year, thereby placing the buyer in physical possession of the land as a tenant.[3] The seller then immediately relinquished their future interest in the property to the buyer who became the new owner. Neither part of this “sale” was the outright transfer of freehold property, rather it was a lease and then a release (of ownership), the name by which this type of deed came to be known. It required two documents, which could become separated from one another over time. If one of them no longer exists it can be difficult to determine if the land was being sold or only leased.

When reading through the 1673 deed, it quickly becomes apparent it is a mass of confusion. Ownership and leasing terminology were both used. “Bargain and sale,” a valuable consideration, a peppercorn rent, lease of a thousand years, and the phrase, “have hold receive,” all appear. Curiously, there is also a phrase near the beginning which states, “…for the better secureinge of a Messuage or Tenement with the appurtences in Newport Pagnell aforesaid…” Given John Jr.’s efforts to retrieve money he believed was owed him from rents, and possibly wanting to stake an even stronger claim to the land on or near the North Bridge, this document may be a failed legal maneuver to prove John’s entitlement to the land.

Given the confusing terminology, it is hard to say exactly what he was trying to do with the property, which is only described as located “near the North Bridge” in Newport Pagnell. George Rawbone was occupying the property, which usually means he’s the tenant, but nothing is said about whether he’s paying rent or not. This may simply be a reference to the fact that John Jr.’s stepmother Martha (married to George Rawbone) was holding the property left to her for life by her late husband John Kendall als. Mills Sr.

If so, this is fudging the legal situation. It places George (and Martha) in the position of tenants rather than holders (ie. effectively owners), which they were through Martha’s dower right which required no rent payment. In 1673, with Martha very much alive, John Jr. had no legal right to lease or sell the North Bridge property unless Martha gave her prior agreement, which is not recorded in the 1673 indenture. Martha legally holds the North Bridge property (and therefore husband George shares that holding with her). If John intends to sell or lease it before Martha dies, he must do it with them, which is what happens in 1681. It appears no sale occurred in 1673, so we must question whether the agreement with John Rawlins ever came to anything.

Renting or Owning?

Another thing to keep in mind is that we don’t know where the Kendall als Mills family members lived during specific years. Nor do we know who was renting from them and living on their property unless that individual was named outright as the occupant. We also do not know if there was only one Old North Bridge property. The land transfers happened in a time when there were few maps, no aerial photographs, and no detailed descriptions of what was on the land. The descriptions we do have are mired in legalese designed to cover everything that could be on the land, not what was.

To be scrupulously accurate, all we can positively state for ownership and occupancy of the North Bridge property is that there was no tenant named in 1654 when the land transferred from Ralph to his son John Sr, but it does state John was ‘dwelling’ there at that date. The 1666 deed of settlement from John Sr. to his intended, Martha Mitchell, declared Edward Sibley was the occupier. John Sr.’s 1666 will also listed the occupier as Edward Sibley. After John Sr.’s death, it became Martha Kendall als. Mills’ dower right property and it remained so even after her marriage to George Rawbone.[4]

Other things we don’t know

In addition, we cannot tell other things about the family and their property:

- if the Kendall als Mills family retained any Sherington property,

- if all of them moved to Newport Pagnell (or if any of them did, besides John Sr. & family)

- where John Sr. and Martha Mitchell Kendall als Mills lived during their brief marriage

- Whether Rafe or any of his children held additional lands or properties in Bucks (or Middlesex)

This 1673 lease muddies the water rather than clearing it. It may have been nothing but a legal maneuver. It’s possible a lawyer thought John already had the legal right to the land or the lawyer or clerk could have even been supporting him or conspiring to help him claim the property. There is simply no way to tell what was going on from this document alone. In any case, the family did not have the Old North Bridge property for much longer. In 1681 it was sold outright and for good, with Martha’s consent, to Jeremiah Smaldridge.[5]

Other posts in this series:

1629/30 Robert Markes to Ralph Kendall als Mills

Land of the Kendall alias Mills Family

1654 Deed of Gift from Ralph Kendall alias Mills to his son, John

1666 Deed of Settlement from John Kendall als Mills to his betrothed, Martha Mitchell

1666 Will of John Kendall (alias Mills)

1670 Chancery Case: Kendall vs. Kendall

1681 Lease and Release to Jeremiah Smalridge

[1] The word “they” was chosen because property owners were mostly men, but on occasion women as well, especially widows or holders of family-endowed property reserved explicitly to them alone during their lives. Even more rarely, women were bequeathed land, though that is mostly among the gentry and aristocracy when women were widowed or unmarried heirs of ancestral holdings.

[2] Tim Wormleighton, Title Deeds for Family Historians (Bury, Lancashire: The Family History Partnership, 2012), 14.

[3] Tim Wormleighton, Title Deeds for Family Historians, 17.

[4] England, Buckinghamshire, Newport Pagnell, Parish Register for Newport Pagnell, 1558-1718, mar Martha Kendall to George Rawbone, 1667, FHL microfilm 1042392.

[5] Smaldridge is the spelling used in the 1681 deed, but it was also spelled Smallbridge, Smalridge, and likely had other variations.