Why would anyone use an alias?

Though not quite the same as the elephant, wrapping our heads around the question of how an alias got into a person’s surname can be almost as baffling as how an elephant managed to get through a doorway and into a room, never mind the whole issue of people ignoring its existence despite the space it takes up. Like a room elephant, alias surnames have been largely ignored by academic researchers and by baffled family historians. Many, with modern sensibilities, might think an alias surname is associated with something nefarious as it can be today. In the period from the mid-1500s into the 1700s when alias surnames show up in many English and a few colonial records, the opposite was usually true.

An alias surname in the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries was more likely to be an “also known as.” It was an extra layer of identification for individuals and families, revealing rather than concealing. There are quite a few reasons a person might take on an alias. This article has many of them: https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Use_of_Aliases_-_an_Overview[1]

The most likely reasons members of the Kendall or Mylles family used an alias surname are:

- Commemoration by descendants of a marriage into a “socially superior” family with the retention of a maiden name of a mother or grandmother.

- Illegitimacy, which could serve the purpose of publicly proclaiming parental origins.

- Rights of inheritance (my personal favorite), and other economic reasons. For example, in a time when deeds/leases were not always recorded, using an extra surname could show a right to land owned by a father. A good example of this might be when a widow remarried and her children took their stepfather’s surname yet retained their biological father’s name as well as proof of their right to inheritance.

- Individuals might also add an alias to obtain an inheritance from a family line in danger of “dying out.”

- Adoption, or marrying into a family.

The Kendall als. Mylles alias

There is no proof yet if any of these reasons apply to the family of Francis Kendall als. Mylles and his brother, Thomas Kendall. (Note-the double or alias surname can also be reversed.) A great deal of research time could be expended without uncovering enough evidence to say which, if any, of these reasons is correct. Or a researcher might fortuitously come across definitive evidence in an archive tomorrow. The reason the Kendall als Mylles family chose an alias is far less important than the fact that they used one for a very long time.

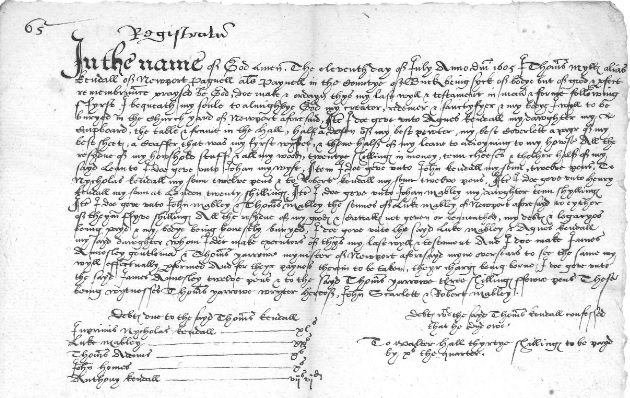

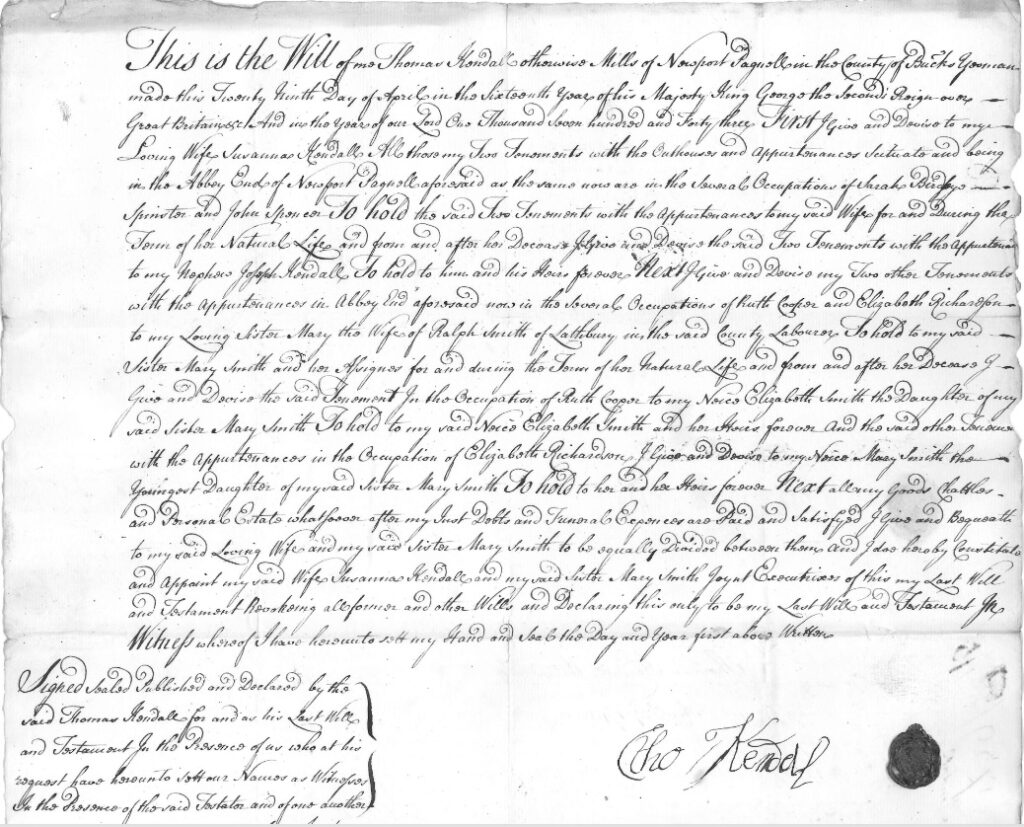

The earliest instance of the Kendall and Miles/Mills alias surname found thus far is the 1605 will of Thomas Mylls als. Kendall of Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire and the latest instance found is a will written in 1743 by another Thomas Kendall als. Mills of Newport Pagnell.[2]

These wills and the records that fall between them document a century and a half of a family using the same alias surname. Perhaps even more importantly, all the documents found which have this alias surname, namely church, property, and probate, are confined to one area of Buckinghamshire.

What type of records use the alias?

Not every member of the Kendall or Mylles/Mills family was identified with the alias surname in every record made on that individual. Recorders may have chosen not to use both names if they felt a person was identified well enough without it or if the person of record chose not to use it. The one thing we are seeing consistently is the alias surname turns up mostly in “official” records. It most often appears in wills, parish registers, and land records in England. The only use of Kendall als. Mylles found in New England so far is the marriage of Francis Kendall als. Miles in Woburn in 1644.[3] None of his children’s births were recorded with the alias and none of his brother Thomas’s documents have it, so Francis may have decided the reason for adopting it no longer mattered in New England, or the New England record keepers were less inclined to use it.

As the FamilySearch Wiki points out, the practice of using alias surnames diminished to the point of obsolescence by the mid-1800s, except in criminal cases, when the use of an alias surname became associated with concealing identity.[4] Preserving a particular last name moved from using an alias surname to using a middle name.

Thoughts on alias surnames from Celia

My research partner, Celia, has read about surnames and alias names and has researched lines which use them. She has given me some of her thoughts on the topic, which are well worth reading. Here they are for anyone who would like to consider more about the use of alias surnames.

I haven’t found any suggested frequency for the use of an alias, and I would be surprised if any historian, other than population specialists, attempted it. I’ve read part of the preface to my Oxford Dictionary of English Surnames, and the section in David Hey’s book, Family Names and Family History, about aliases. This led me to read some of what came before and after the alias sections in both books, which showed me how immensely complicated the development of surnames (and given names) was. What we might regard as an ‘alias’ might be recorded in multiple ways during the period before (in England at least) surnames became rock solid for everyone. By the time of 1605 Thomas’ birth, which was perhaps in the 1530s or so, there was still some fluidity on the surnaming front. I personally wonder if the period in which we see aliases used ‘fairly often’, mainly stopping after the 17th c., was one where people hadn’t yet fully adapted to a single birth surname used (for men at least) throughout life unto death and passed on intact to children.

While aliases did happen “reasonably often” in the 16th and 17th centuries, each one tended to be a one-off, unique to the family line in question. In my opinion, it’s rare to see the same alias being used by unconnected families, if it ever happened at all. David Hey makes the point that aliases, or other forms of recording alternative names, are extremely useful to the finding of an ancestry in a historical period when there are few sources to help.

I saw that it’s possible people we see with an alias surname never used it themselves, were never known by the alias in their community and that it was entirely a ‘documentary record’ by one or more scribes. This could help explain why an alias generally lasted only one or two generations, the vital family events recorded perhaps by a single scribe/authority, or just one or two, who personally knew the reason behind it (illegitimacy, inheritance, etc). The authors of the books emphasised the difference between ‘everyday use’ (personal and community identity) and what was written in official records, where it could be seen as vital to note another surname, or other details, for whatever reason. Considering that the Kendall alias Mylles we’ve mostly looked at so far were non-literate, then they may have had little or no say in what was recorded.

Conclusion

Using the clue of the Kendall alias Mylles surname is vital to the search for the ancestors of Francis and Thomas Kendall. Its rarity and the very small geographic location where it is found are our best clue to identifying the family in England. Creating an alias surname was not a home-grown American colonial tradition, rather it was used in New England only when it was imported from England. Myths have grown up around Francis’s use of an alias, but it is not because he was kidnapped as a child (he immigrated as an adult), not because he wanted to conceal his location from his family (his brother Thomas likely came with him), and not because he committed a crime and was on the run. We need only know taking an alias was an uncommon, but real, English naming custom and his family followed it. It’s possible we may one day find the reason the family chose the alias surname, but for now we can only theorize why it happened. What we cannot do is ignore a clue this big.

[1] FamilySearch Wiki, (www.familysearch.org/wiki), “Use of Aliases-an Overview,” rev. 13:39, 22 February 2022.

[2] England, Buckinghamshire, Buckinghamshire Council Archives (https://www.buckinghamshire.gov.uk/culture-and-tourism/archives/ : accessed May 2023), 1743 Will of Thomas Mylles alias Kendall of Newport Pagnell, RO ref: D/A Wf 1 6, probated 1605.

England, Buckinghamshire, Buckinghamshire Council Archives (https://www.buckinghamshire.gov.uk/culture-and-tourism/archives/ : accessed May 2023), 1743 Will of Thomas Kendall alias Mills alias Kendall of Newport Pagnell, RO ref: D/A/Wf/92, probated 1759.

[3] “Massachusetts Vital Records, 1620-1850,” database with images, American Ancestors NEHGR (www.americanancestors.org : accessed 9 May 2023), Francis Kendall & Mary Tidd.

[4] FamilySearch Wiki, “Use of Aliases-an Overview,” rev. 13:39, 22 February 2022.