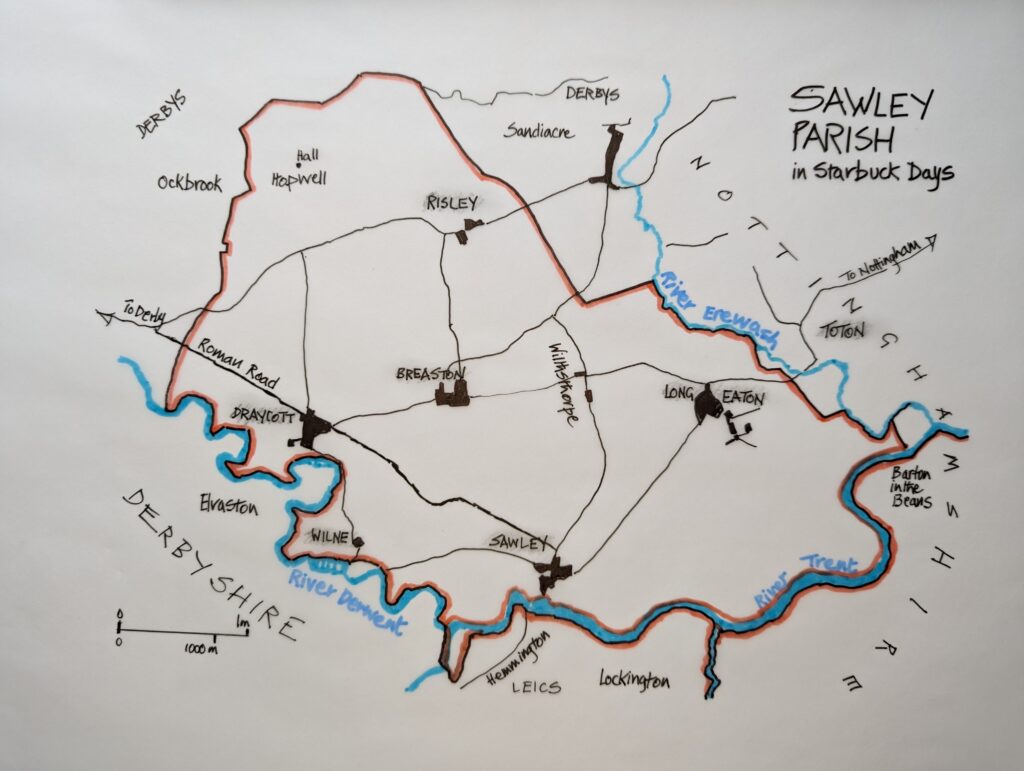

The large and complicated parish of Sawley encompassed nine settlements. We know for sure that Starbucks lived in three of them: Long Eaton, Draycott and Breaston. As residents of Long Eaton, they would have attended the parish church, Sawley All Saints in Sawley village, while Draycott and Breaston Starbucks walked the mile or so to their church of Wilne St Chad.

We do not know whether Starbucks lived or worked in the other four settlements of Sawley: Hopwell, and Risley with Wilsthorpe and Woodhall Park. However, they were part and parcel of Sawley life in the 1550-1640 period, known inevitably to Starbucks like the back of their hands. Some may have lived in these places over the many centuries, unknown to us now simply through lack of records.

Hopwell was a Liberty that came under Wilne St Chad’s chapelry within Sawley parish. It was also a manor separate from Sawley’s, held from the late 14th century until 1661 by the Sacheverell family. In the 16th century, they built a substantial seat here – Hopwell Hall. This was demolished and replaced in 1720 by a larger version set in a 90 acre park by Henry Keys, who had inherited the old hall from Jacynth, the last Sacheverell at Hopwell.[1] We found no records directly connecting Starbucks to Hopwell.

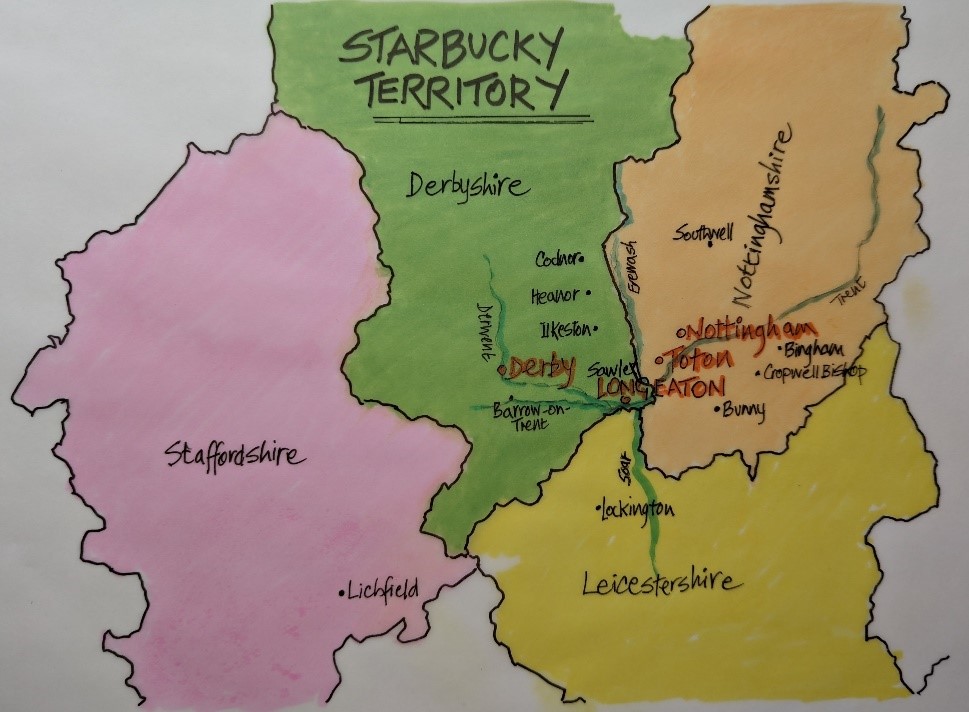

Continue reading “Starbucky Territory: Risley, Hopwell, Willsthorpe, and Woodhall Park in Sawley parish, Derbyshire”